Taking a moment for a little shameless self-promotion

I posted this list of my other projects last May, so I thought it was time for an update. These are all ways to support what I’m doing, if you would like to do so. And, of course, you can become a paid subscriber here:

I first encountered the term “hoardings” in England, where I took it to mean the same thing as a billboard. But “advertising hoardings” refers to the large boards erected around a construction site, which can prominently feature printed graphics and designs. And that seems an appropriate description for today’s post.

Last year, I discussed the importance of writing consistently, mentioning that I like to schedule several weeks’ worth of posts in advance so I don’t feel like I’m rushing to meet a deadline. But as of this post, I’m only scheduled for the next two weeks … and while I do have several things in draft, it feels a little bit like a construction site in my draft folder.

So why not use this dusty space to advertise? And what should I advertise? How about me?

Around my 45th birthday, I realized there were several things I wanted to accomplish before turning 50 – first on the list was to take my favorite stories from the blogs I posted in the early 2000s and publish them as a book. My friend Johanna offered to be my editor, and in 2016, we published “Tad’s Happy Funtime” – named for my early blog.

My first (and so far, only) fiction sale was a story called “Silver,” published on the Dunesteef Audio Fiction Magazine podcast in 2008.

At the time, I was inspired to write by Escape Pod, the weekly science fiction podcast, which launched in 2005. The company has expanded to five podcasts – science fiction, fantasy, horror, Young Adult speculative fiction, and Catscast…which is cat-based speculative fiction. As you would expect.

Escape Artists, Inc. became the Escape Artists Foundation in 2023, a non-profit organization dedicated to producing free, listener-supported stories every week and paying the creators who make it all possible. If you like fiction, it will cost you nothing to visit their company website, EscapeArtists.net, and look around!

Since 2016, I’ve been an associate editor for their Pseudopod Horror Fiction podcast, where, in addition to reading submissions (an adventure in itself), I’ve hosted and narrated several episodes. You can find links to the episodes I’ve been on at this link.

In September 2021, I narrated Escape Pod 802: Sentient Being Blues, a story about a Russian mining robot that gains sentience and starts singing the blues. I had a ball doing it, and now I get to claim (factually) that I’ve appeared on the same podcasts as Anson Mount and Linda Hamilton!

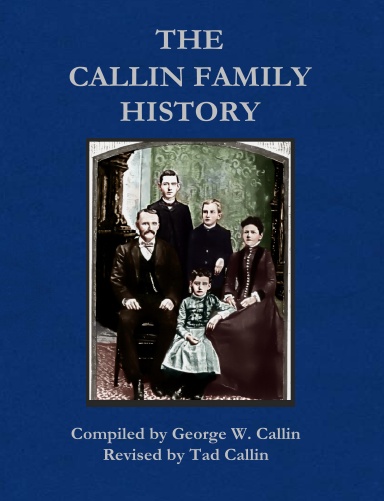

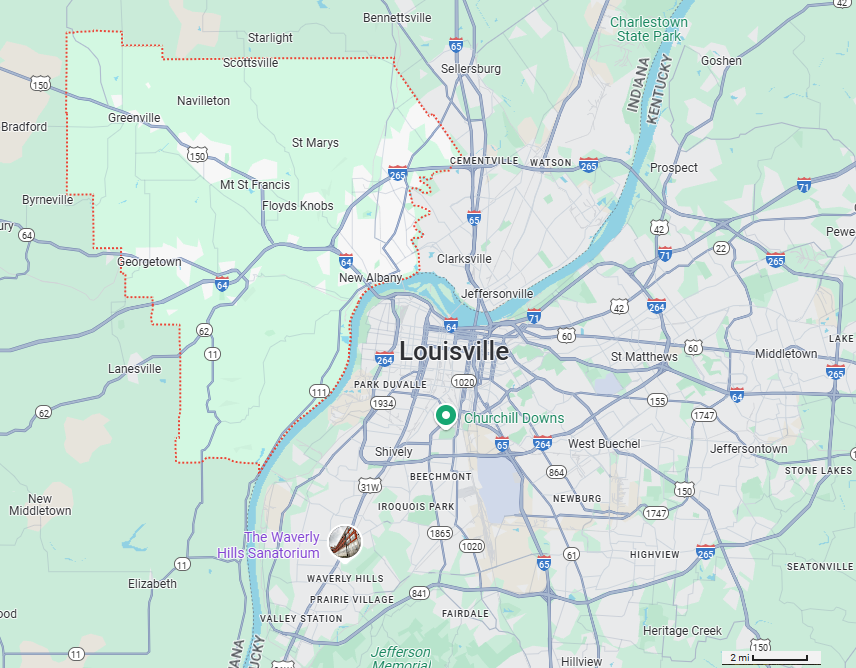

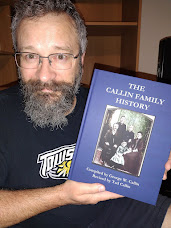

Long-time readers will know that in March 2022, I published my updated Callin Family History on Lulu.com:

This is the one I worked on for seven years – it has a BLUE cover with a portrait of the family of George W. Callin (restored and colorized by Claudia D’Souza, the Photo Alchemist).

I was inspired to start that project by the original 1911 Callin Family History:

This is a replica of the original Callin Family History published by George W. Callin in 1911. It has a RED cover and is much smaller than my Big Blue update. If you’d like a copy of this one, you can get it in either paperback or hardcover:

link to the Paperback version

link to the Hardcover version

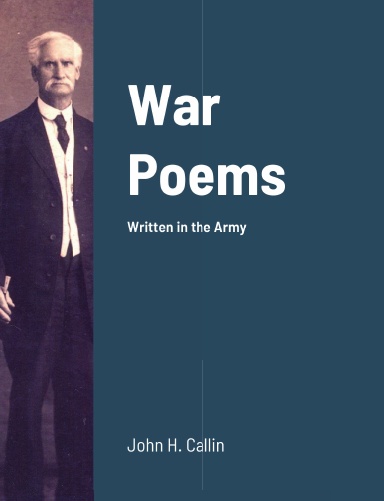

And then we have:

This was my secret side-project for much of 2021. My aunt Vicki inherited a book of poetry written by her great-grandfather, John Henry Callin, and she and I collaborated on transcribing it and editing it for publication.

(The link to War Poems will ask you to verify your age due to “explicit content”; that’s because there are grisly descriptions of John’s wartime experiences in some of the poems.)

Last year, I launched another Substack, All Kinds Musick, where I try to connect with the “why” of the broad range of musicks that I love. Occasionally, I manage to write something there that has to do with family stories, so you might have seen a couple of cross-posts.

Are you still with me? That’s very kind. I guess the only thing left to promote is my SoundCloud… which I recently learned still exists!

I only posted a few recordings to try out the service, but I was pretty proud of these two.

“Birthday Disco” is a song I wrote for my girlfriend in 1991 and recorded in the then-new electronic music studio at Glendale (Arizona) Community College.

“Beyond Belief” is probably still my favorite Elvis Costello song, recorded at home in Maryland around 2010.

Got any projects you’re proud of? This seems like a good place to mention them!

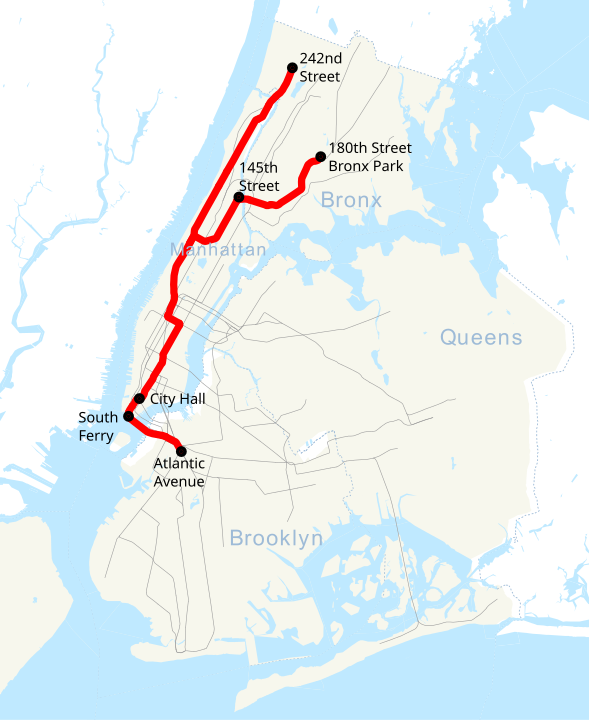

Next time, we can go back to talking about family history.