My kids have eight Great-Grandparents. That’s not unique – everybody does!

But if you look at family trees as a generational benchmark, my kids fall mostly into “Generation Z” and their great-grands fall into what is known as “The Greatest Generation” – the people who fought back the Axis Powers in World War II.

I find this interesting because their Great Eight were born within a relatively tight cluster of years, beginning in 1920 and ending in 1928, a trend which is statistically unlikely to continue as we go further back. They also came from a relatively small number of U.S. states: most from Iowa, two from Ohio, and one each from Minnesota, New Jersey, and Arizona.

The G.I. Generation

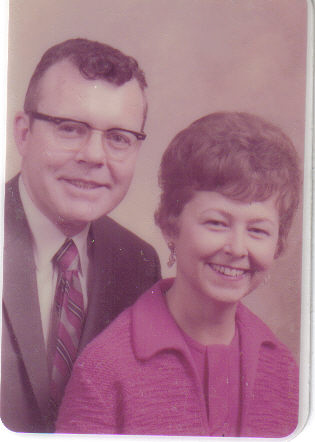

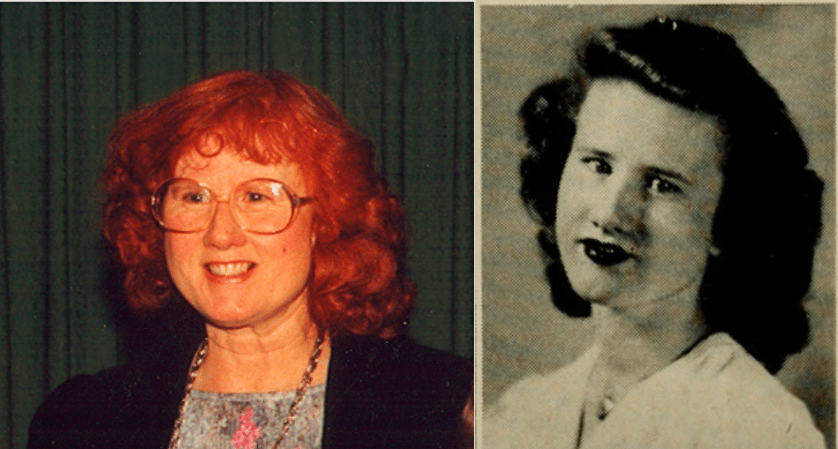

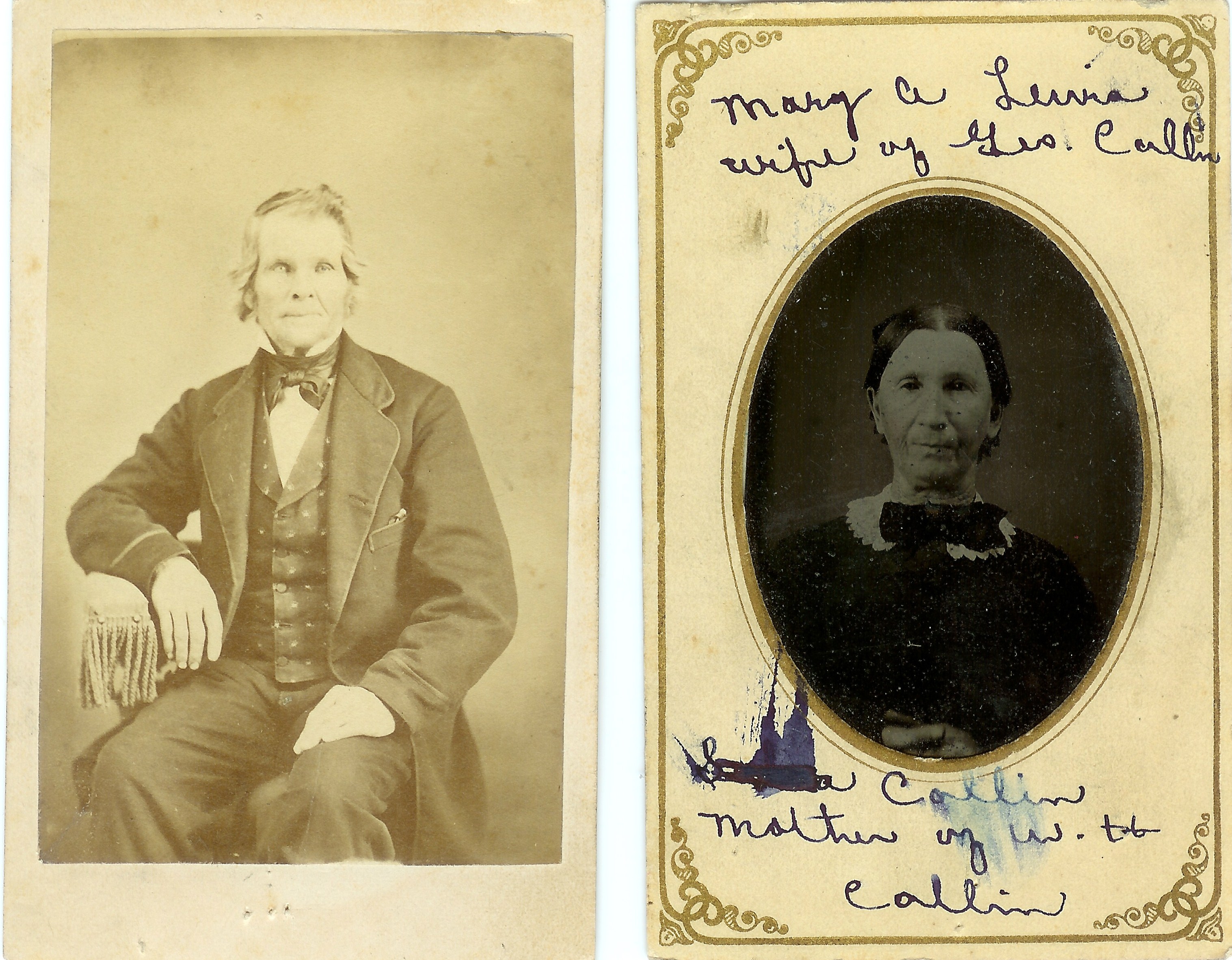

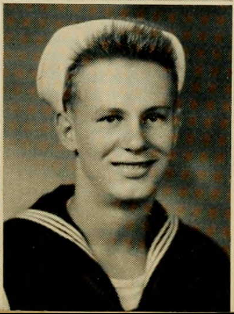

Three of the four Great-Grandfathers we’ve talked about (Bob Callin, Russ Clark, and Bud Holmquist) were born in 1920, with Bob the youngest (December), Bud born in September, and Russ the oldest, being born in March. The odd man out was Bob McCullough, who was born in 1927 and is the only one of the four who was too young to fight in World War II. (He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1946 and 1947, and served a tour in the Korean Conflict.)

Each of these men married someone slightly younger than themselves. My grandmothers, Nancy and Alberta, were both born in 1925; my wife’s grandmothers were both older than mine (Merilyn was born in 1923) and younger (June was born in 1928). Merilyn and June were both married at 19, while Alberta was nearly ancient (according to the way she told her story1) at 20, and Nancy was only 17!

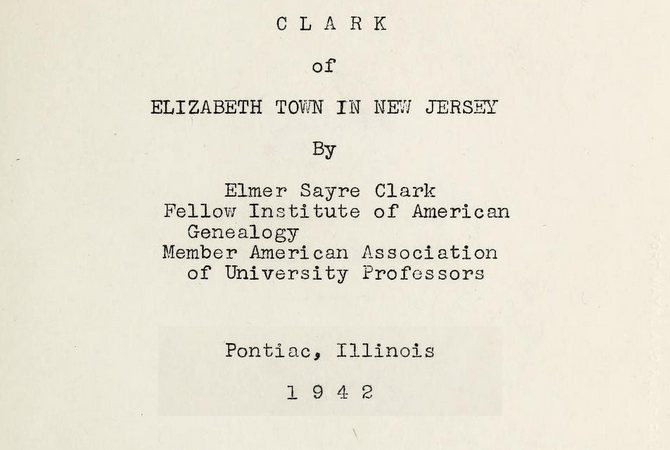

All eight of them came through the Great Depression, but here their individual experiences differed somewhat. Merilyn was the daughter of an Omaha-area businessman who owned a filling station and oil company, and she married Bud, the up-and-coming son of a Swedish immigrant. Bob Callin’s family also had some success with teaching and running businesses in Ohio before moving down to Florida to build cottages near Orlando. Bob McCullough and his eventual wife, June, came from families that worked on the railroads, and Alberta’s father was a New Jersey grocer, which meant they were probably shielded from the worst of the Depression. Nancy’s father and mother struggled in their early years, but ran a dairy and sold beef in Arizona during the 1930s. It was Russ Clark’s large family who may have been worst off during those years, and I do remember him often talking about the hard times his mother had feeding a dozen children.

Politics and Religion

While you can often find references in old local histories to people who identified with a particular political party, I get the impression that most people in this generation didn’t make their politics as central a part of their identity as people do today. Similarly, their religion wasn’t a matter of identity as much as it was a factor of how the community organized itself.

I’ve talked before at some length about the fact that both of my grandfathers were ordained in the Southern Baptist tradition. Neither of them grew up in a Southern Baptist church, as far as I can tell. When Bob and Nancy met, Nancy attended the First Christian Church in Glendale (the full name of the denomination is “Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)”), where her mother was a charter member. Alberta’s family were Methodists, and many of the men on Russ’s maternal side, the Reynolds, were itinerant Baptist preachers, but Bert and Russ became Southern Baptists during the 1950s.

Bob McCullough and June Shuffler were married at Our Savior’s Lutheran church in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and as far as I know, that’s the church they grew up in. In contrast, Bud Holmquist’s family was also Lutheran, but Merilyn’s family was Christian Scientist.

All Families Great and Small

Several major trends affected families between the generations of the Great Eight and their children. Public sanitation – like water treatment programs, public hygiene, and local vaccination efforts in some states – and industrialization after the Civil War meant that “farm families” did not have to have as many children to guarantee that some would survive. Fewer children died of childhood diseases, and as families moved to cities where the men found work in factories, they didn’t need large families to help with the family farm.

Here is a table showing the number of children in each family for two generations, and the range of birthdates for those children. (In the “siblings” column, I counted the person along with their siblings, so Bob Callin and his two siblings give us three total.)

| The Great Eight | Siblings (span of birthdates) | Children (span of birthdates) |

| Bob Callin | 3 (1907-1920) | 2 (1943-1946) |

| Nancy Witter | 2 (1921-1925) | |

| Russ Clark | 11 (1899-1920) | 3 (1947-1956) |

| Alberta Tuttle | 2 (1920-1925) | |

| Bob McCullough | 9 (1908-1927) | 6 (1949-1967) |

| June Shuffler | 2 (1926-1928) | |

| Bud Holmquist | 4 (1915-1923) | 2 (1945-1950) |

| Merilyn Martin | 3 (1920-1928) | |

| Total | 36 (1899-1928) | 13 (1943-1967) |

I notice that except for Bud and Merilyn, who were “middle children” (Bud was 3rd of 4 siblings), everyone was the youngest in their family.

Of the 36 children in the families of the Great Eight, only 4 died in infancy.

Different Circles

I never met either of my wife’s grandfathers, and only met her grandmothers a few times. Both sets of grandparents knew each other, but I don’t think they saw each other very often. Bob and June most likely met Merilyn at their children’s wedding in Council Bluffs, but since the McCulloughs lived in Minnesota, I doubt they interacted much beyond that. And Bud was in prison by then and had no contact with anyone after the mid-1960s, as far as I know.

Russ and Bert did know Bob and Nancy, but despite all they had in common, I don’t think they spent much time together. Bob and Russ were both Southern Baptist ministers, but they were very different in how they thought about the world and how they practiced their faith. Both couples spent a lot of their time in RVs exploring the Southwestern United States, but for Bob and Nancy, this was more of a hobby, while Bert and Russ made their home in their campers and treated their travels as a calling.

I find it interesting to think about how different these eight people were, and how unlikely and random it is that their children met each other and decided to have families of their own. As we continue this journey, I expect we will see examples of families who lived closer to each other and shared a lot more in common than the people in more recent generations do, even as the different family groups become more distant from each other as we go back in time.

As we continue this journey, we will have to learn more about our history to understand the people we study. We will have to get to know them through the context of their time, use what we know about ourselves to imagine them living through events, and puzzle out what choices they made that led to us.

Next week: we start with my “Great Eight” – the first half of my childrens’ Sixteen great-grandparents!

You must be logged in to post a comment.