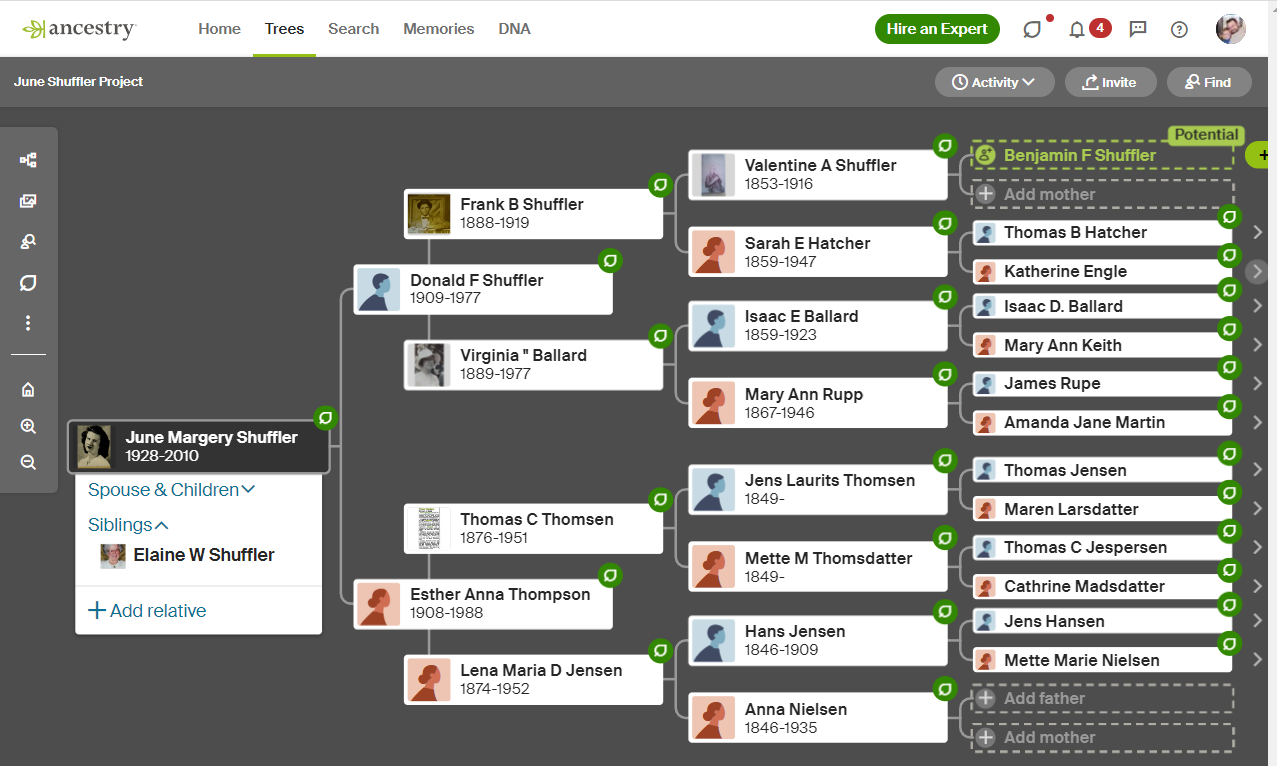

posted Friday, November 21, 2014

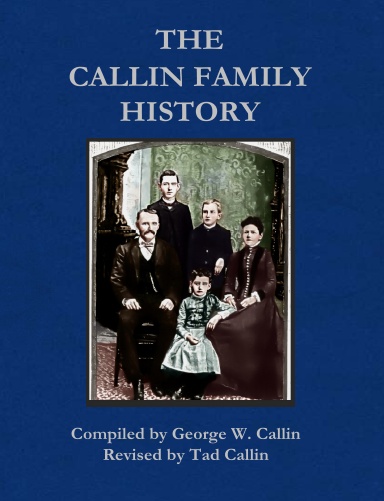

This piece was adapted for this blog from a longer two-part piece on my Tad’s Happy Funtime blog. That version spends more time on me than is proper for a biographical sketch of my grandfather, Russell Hudson Clark, Sr. (1920-2002), but if you’d like to see that longer version, part one is here: A Fire in the Desert

The preacher roamed the wilderness of the desert Southwest for 50 years in a series of new and used recreational vehicles, his wife by his side, always seeking receptive souls to bring to the Lord. He raised a son who went to Vietnam and two daughters – all three raised sons of their own. He built houses, sank wells, raised chickens and rabbits, saved souls, started churches – and moved on, always moved on.

His name was Russ Clark, and he was a big man with a big voice, a broad smile, a ready laugh, and a proverbial fire in his belly. He once joked that this was why he ate so much when he visited us, but that was more likely a side effect of being the youngest of 12 children raised in the South during the Great Depression.

His hair, what was left of it by the time I knew him, was usually a close-cropped white stubble that seemed to grow wild and wispy overnight. I thought of him as a bald man, but he always claimed to need a haircut.

“Grandpa,” I would exclaim, “You’re bald! Why do you need a haircut?”

And his laugh would boom, and he would start to relate to me a tale about Jesus telling all men to keep their hair off their collar, not like those… but Grandma would usually swoop in with the clippers and a towel, and hurry him off to our patio for a trim before he could get much further.

He traded camper vans up for RVs, traded the RVs up for pickups with fifth-wheels, and traded the trailers up for mobile homes on an acre of property before deciding he had tied himself down with too many possessions and scaled back down again. No matter where he lived, you would find Grandma with her box of mementos, her organ, their dog, and her quiet hope that someday they would find the right home.

One thing about desert life is its innate mobility. Plants’ roots never run deep – they run shallow and broad. Animals may dig in and hide during the heat of the day, but they know to stay on the move if they want to find shade and water. One place Grandpa could always find some shade and water was under the tree in our driveway.

When Grandma and Grandpa showed up, it was almost always a surprise to us kids. Mom learned not to give us any warning that they were coming to visit, or we would stake out the couch by the big picture window and drive each other crazy with anticipation, shrieking “They’re here! They’re here!” at every puff of dust on the washboard that was 89th Avenue.

And they would finally roll in, pulling up under the skinny poplar tree where Grandpa would jack, level, and brace whatever mobile domicile they were currently living in, and hook up water and electricity. He’d run a hose from the sewer line to the poplar tree, and remind us kids that if we used their toilet, only to “run water” in it. When we were little, he’d explicitly tell us, “Only pee-pee and wee-wee in there! No poop-poop!” and we would giggle at the naughty nonsense words and repeat them daringly until we remembered that Grandma was waiting inside.

Most of the time, we could take turns sleeping over in the Camper; no matter what the actual vehicle was, it was always “the Camper” to us. Our favorites were the cab-over motorhomes with their inevitable forward and side windows. I’d fill every spare inch with Star Wars men, posting guards at the corners and locking imprisoned rebels in the cup holders. My sister would pasture her My Little Ponies on and around the dining table. Meanwhile, the grown-ups would stay inside with sweating glasses of sweet sun tea, talking about trade-in values, equity, and whatever else grown-ups discuss when the kids are out of earshot.

None of these visits ever lasted long enough for my sister or me, but Mom and Dad seemed to uncoil a little bit whenever the clouds of dust would follow the caravan du jour down the road toward their next stop – usually my cousin’s house a few miles away. Looking back, I can see how my dad, who was always happiest building and tinkering with his handy projects around the property, might have looked forward to not having his father-in-law offering advice on how to build and tinker better. And since they were mom’s parents, I could see how maybe there were lingering childhood issues that every family has that made her feel progressively less in control of her own home until the visits were over.

They never said anything to us about it, because they would never say an unkind word about anyone to us. But I think now that maybe the mornings after Grandma and Grandpa drove off after each visit might have been the mornings that Mom’s old Beatles, Monkees, and Lovin’ Spoonful records came out for a spin – replacing Kate Smith’s “How Great Thou Art” and Barry Sadler’s “Ballad of the Green Berets” which had seen more prominence the previous few days.

Whatever the adults’ issues may have been, I remember treasuring the stories Grandpa told us. If Grandma left him alone with us for any length of time, we would prod and pester him to tell us stories about growing up in Kentucky and Arkansas, and when he did, we would sit around him, raptly hanging on every word. This happened most often on Sunday afternoons, after church and the big chicken dinner that Mom and Grandma would prepare. I remember sitting close to him, despite the inescapable odors of dust and sweat that plague a big man who spends long days driving Arizona back roads. I remember feeling full of chicken and listening to him tell adventurous stories about the things that his brothers got up to or cautionary tales of drinkers and smokers who ended up badly.

My personal favorite was a memorable tale about the time a young Grandpa had found a perfectly good hat floating on a vat of sheep dip when he took a shortcut through the stockyards. He wore it proudly down the main street, only to have a woman run screaming out of her house, calling the police and demanding that he show her where he found it. When the police dragged a pole through the vat of sheep dip, they found the woman’s husband – dead and drowned. He had evidently wandered through the stockyards after a night of heavy drinking and fallen in. Sometimes, when he ended the story, Grandpa would tell us that the woman let him keep the hat – and he would point at his sun-bleached ball cap with the enormous grin of a champion spinner of tall tales.

Grandma was never comfortable with Grandpa’s insistence on filling our heads with nonsense, so he would frequently placate her by telling us Bible stories. I always figured the Bible stories came naturally to him because Grandpa was a preacher.

At least, he would talk about being a preacher; and once or twice, he was invited to give a sermon at our church. In school, when our religion class covered the revival movements of the 1800s, I knew exactly what they were talking about when they described the hellfire and brimstone of the tent revivals, largely because of the impression that my Grandfather made on me from the pulpit. He lit up in front of a congregation of any size or composition, and his oratory would grow olive branches and wind its way along the corners of our plain, unadorned sanctuary turning our little Southern Baptist church into a cathedral or a great tent.

It was something of a mystery to me why he didn’t have a church of his own, but I figured out that there is a big difference between being a “preacher” and being a “pastor”; it’s rather the same difference between being a revolutionary and running a government after the revolution is over.

That revolutionary Grandpa would sometimes run out for a gallon of milk, and come back hours later relating how he had spied a young man “with an earring” who had clearly needed to hear the Word of Jesus. Or he would leave Grandma with us while he went “visiting” – coming home late in the evening, bursting with energy, and planning to move back to Phoenix and start a revival that would sweep the city!

Even when he did “find a church home,” it never seemed to last. There would be excitement; property would be purchased or rented, and funds raised. Ground would be broken, and promises would be made. But eventually, almost never longer than six weeks along, the enterprise would evaporate and Grandma and Grandpa would pack up and drive off disconsolately, shaking their heads, and sadly bemoaning a general lack of faith and unwillingness of people to hear the Word of the Lord.

Not that there wasn’t something to Grandpa’s side of the story, but it’s fair to say that there were several notions harbored in his heart along with his extensive knowledge of Bible stories and personal morality tales. When I got older and read about the John Birch Society and Barry Goldwater, and started seeing “conservative” radio and TV hosts gaining popularity in the early 1990s, I recognized many of the ideas that Grandpa had tried to teach me over the years when Grandma and Mom were out of earshot. Like the time when I was 9 and deeply into dinosaurs, he waited until we were alone in the living room to tell me that Satan had placed their bones in the ground to confuse scientists and to test our faith. Or when the space shuttle Challenger exploded and he ruefully reminded me that the space program was just man’s foolish attempt to build another Tower of Babel and that the explosion was God’s way of reminding us to stay focused on Jesus.

At the time, I hadn’t explored any of this very deeply. To me, Grandpa was simply one of the most colorful and admirable people I knew. On balance, he made me feel loved more than judged, and he was clearly proud of me. Maybe his stories exaggerated some details, and maybe some of his beliefs about science were on the questionable side, but he instilled an appreciation for narrative and a love of words in me that I still cherish. I was enthralled by the power of his storytelling, and I learned that his engaging tall tales about growing up in the South and his ever-evolving stories about his exploits serving in the Navy during World War II were, if not factually precise, intended as morality plays. I doubt it was his intent, but he taught me the beautiful and awkward relationship between fiction and truth.

Sometime in the dim, early reaches of my memory, Grandpa had a nasty fall. He was working as a building inspector in downtown Phoenix and fell off of a building he had been climbing. His knees were destroyed, and he spent a great deal of the rest of his life in and out of the VA hospital for various surgeries to repair or replace his joints. It happened that one of his visits occurred during my junior year of high school and coincided with a new knee replacement at the hospital where my girlfriend’s neighbor worked as a nurse.

As was expected, when Grandpa came home from the hospital he began to regale us excitedly about what a blessing it had been for him to be the instrument of the Lord in that place; how he had prayed with all of the nurses and Saved them all – reinforcing his perception that there was a Higher Purpose to his suffering, and that Jesus was using his pain to win souls.

He saw himself as a light in the desert at night, trying to show people the way.

But when I asked my girlfriend’s neighbor, the nurse, about Grandpa’s story, she told a slightly different version. “Oh, yeah,” she said, “I remember Mr. Clark. He wouldn’t let us change his bedpan or give him any meds until we prayed with him. I accepted Jesus eight times, just so I could finish my rounds.”

Perception differed from reality in the harsh light of day.

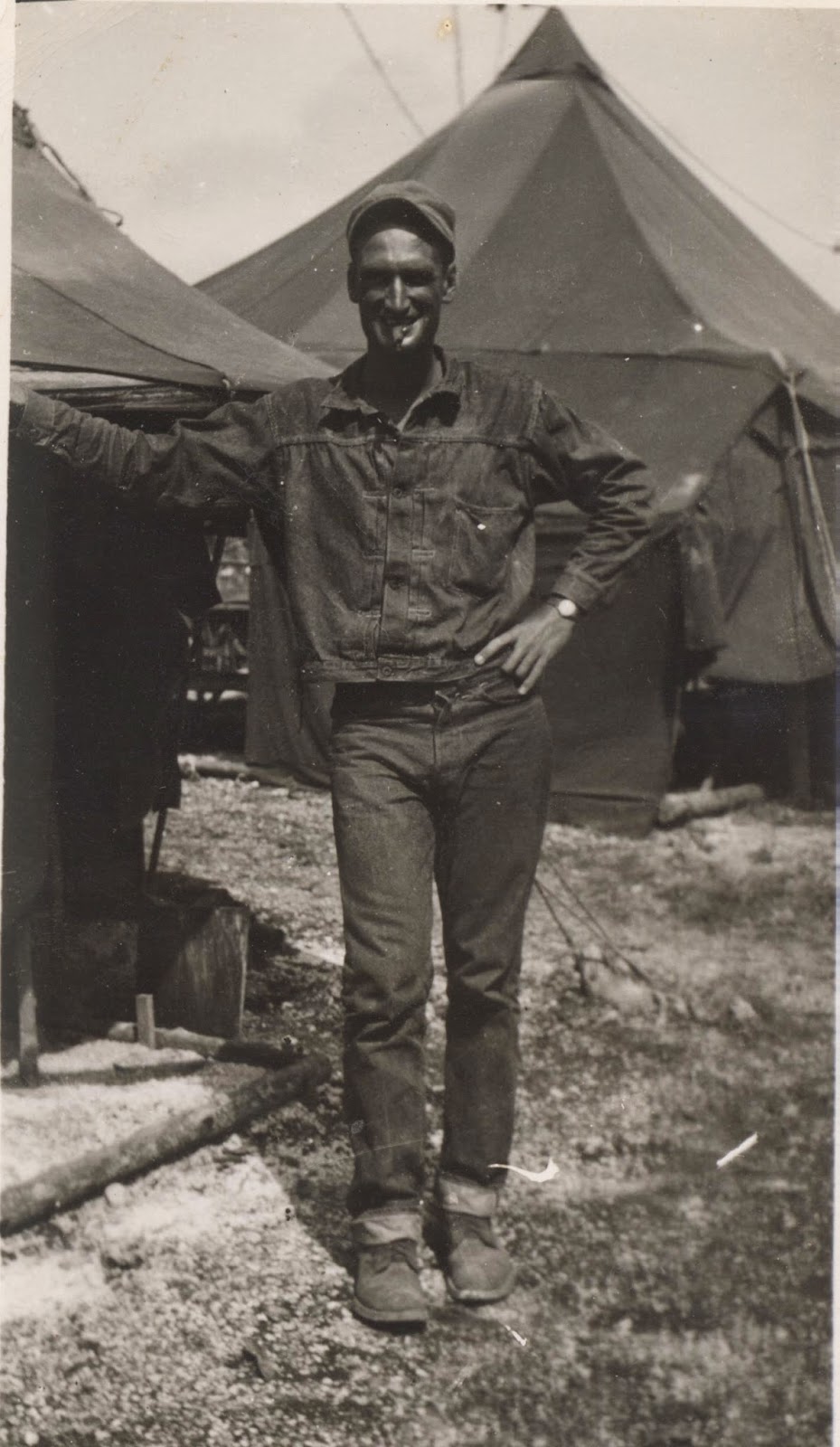

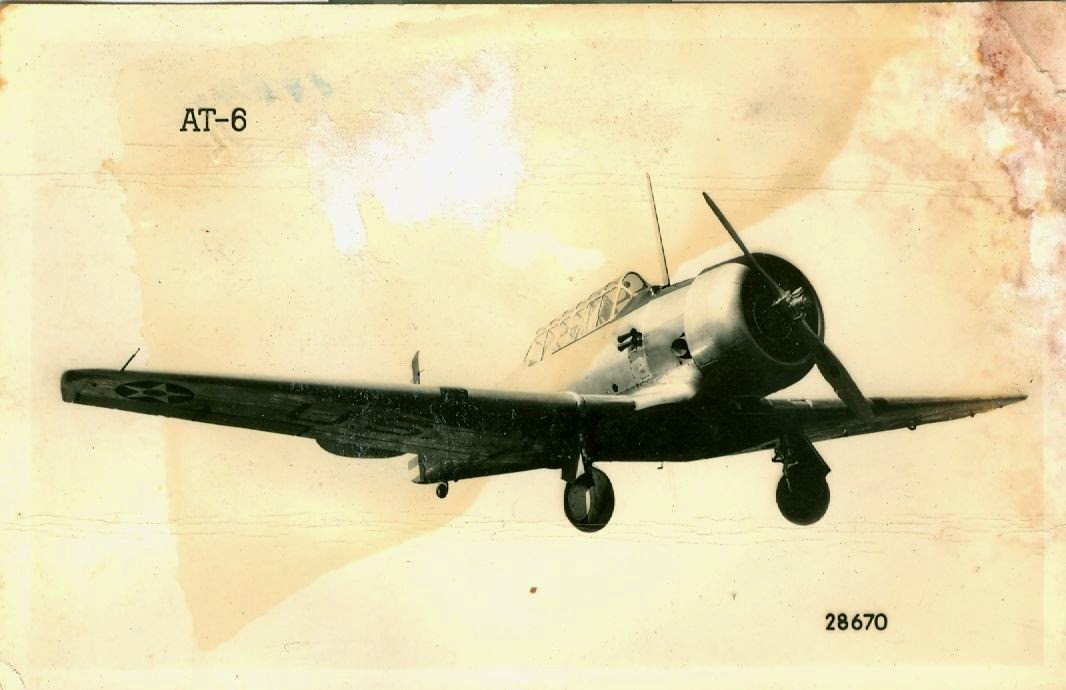

When he found out I was joining the military, he was proud, and he pulled me aside to tell me about his experiences. Not the stuff he told me when I was just a kid, mind you – he wanted to warn me of the “traps” he had fallen into as a serviceman in the U.S. merchant marines; his cocaine and heroin habits (which I had never heard him mention before) on top of his drinking and smoking (which I had). He told me how he had been singing in a night club on shore leave in Italy, and had been approached by a U.S. Army Major who wanted to recruit him to sing in his USO band – but that Major, one Glenn Miller, had disappeared in Africa before the transfer papers went through. Needless to say, the details he told me didn’t add up with official accounts, but I understood by then that they were true enough for stories and that he was really telling me he loved me.

Grandpa passed away in 2002, about a year after I returned to Arizona from serving overseas in the Air Force with my young family. I had known his health was declining for a while, so as soon as we returned to the States, we arranged to visit Grandma and Grandpa in their RV, which was hooked up on the San Carlos Apache Reservation outside of Peridot, AZ.

I had told my wife many of my stories about him, and she was almost terrified to meet him. She knew he had strong opinions about tattoos and how a wife should behave, and while she’s pretty tough and uncompromising herself, she didn’t want to be resented by anyone in my family. But her fears dissipated when they finally met. Grandpa was overwhelmingly sweet, complimented her tattoo, and dandled the baby on his knee (which had recently been replaced again) while recounting his adventures on a Liberty ship taking lend-lease materiel to Murmansk through a German submarine convoy in 1941.

We had a wonderful (if short and hot) visit. Kate was relieved that Grandpa hadn’t criticized her or tried to Save her – but she wondered why he kept calling her “Karen.” The explanation for the name slips and the apparent change of character was horrible and simple: Alzheimer’s.

It is a horrific thing that a disease like this can alter your perceptions without you knowing it. The more we learn about the human brain, the more we understand that it is a delicate marvel and how easily it can be deceived. We learn more all the time about how memory works (or doesn’t) and how unreliable we are as eyewitnesses. I had long known that, in the harsh light of day, I had to take Grandpa’s stories with a grain of salt, but Alzheimer’s magnified the problem.

Finding out years after the fact that things he said to me, and things he believed were true, could have been due to changes in his brain forced me to reevaluate everything I thought I knew about him. It was hard to sort out, but in the end, while it’s impossible to know how much the disease had to do with altering his basic character, I choose to see the sweet man we said goodbye to as the “real” Grandpa. It doesn’t matter what made him do and say things – what matters is that he did his best with what he had.

He chose to roam the desert doing what he thought was right. I choose to perceive him in the best possible light – warts and all, flaws proudly on display. After all, a fire in the desert may cast shadows at night that disappear in the harsh light of day; but without it, the night can get very cold.