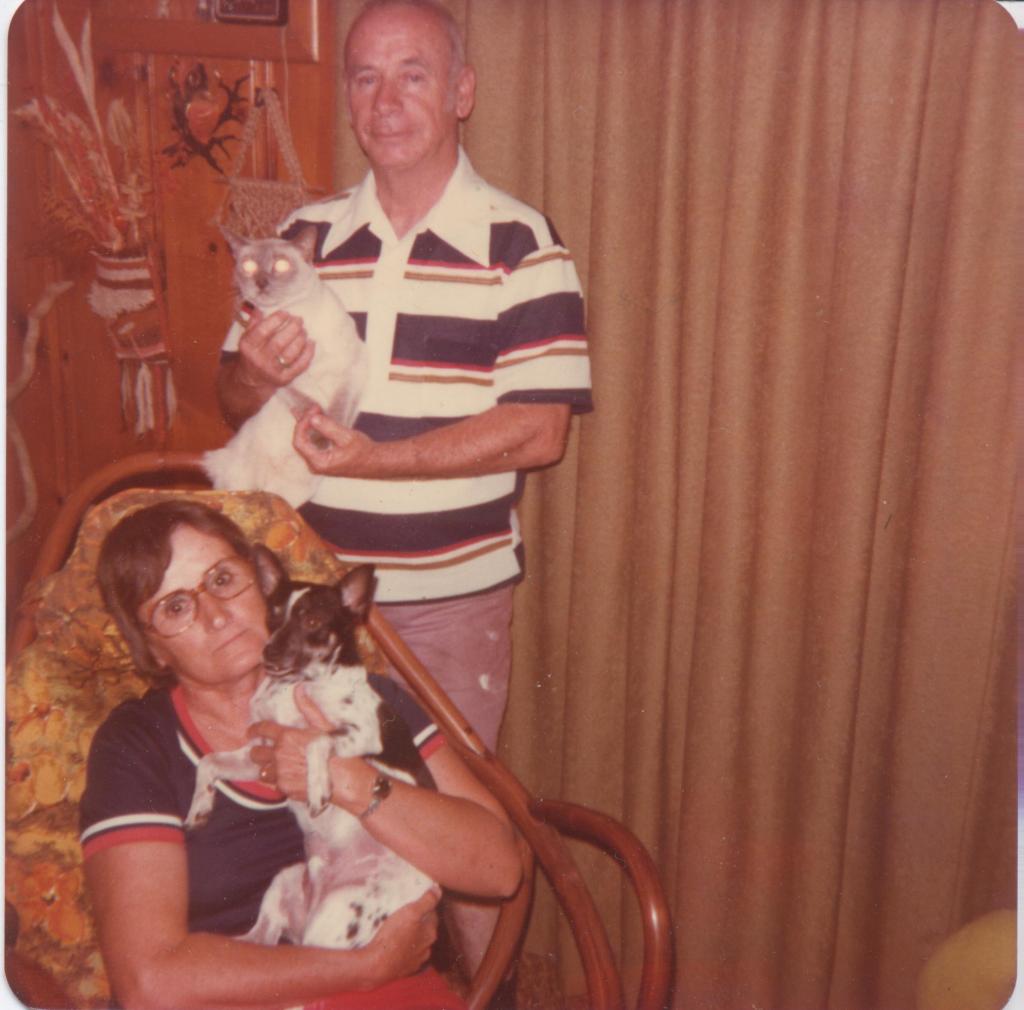

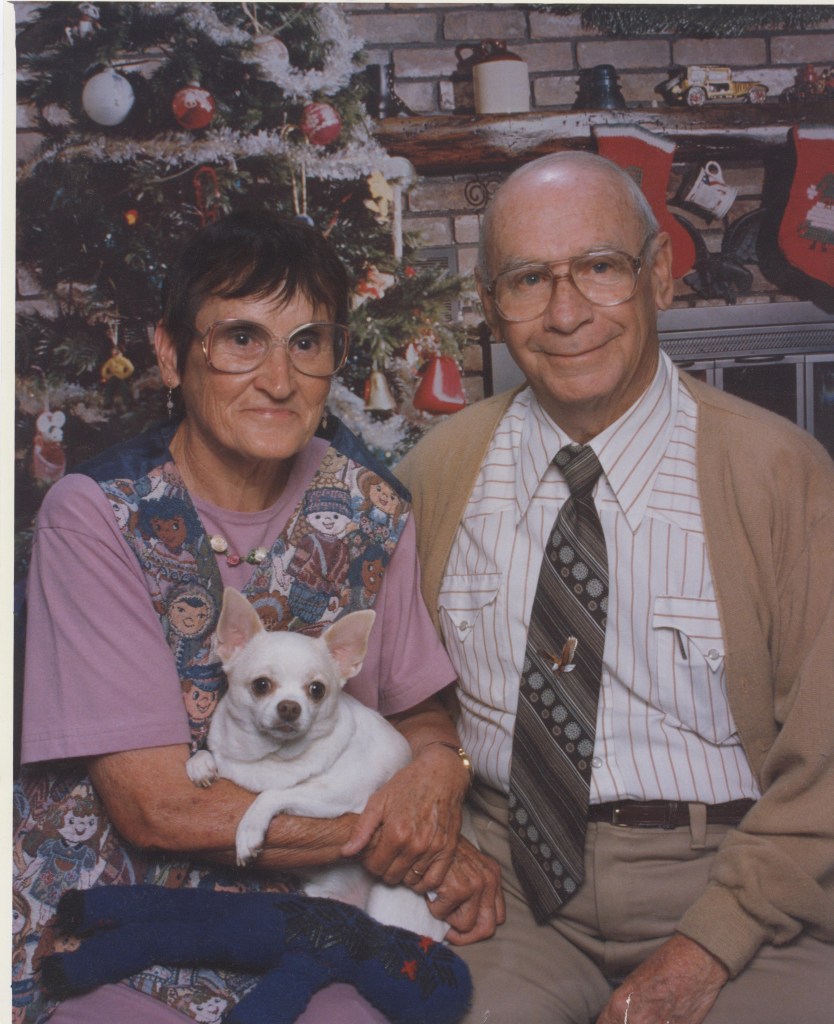

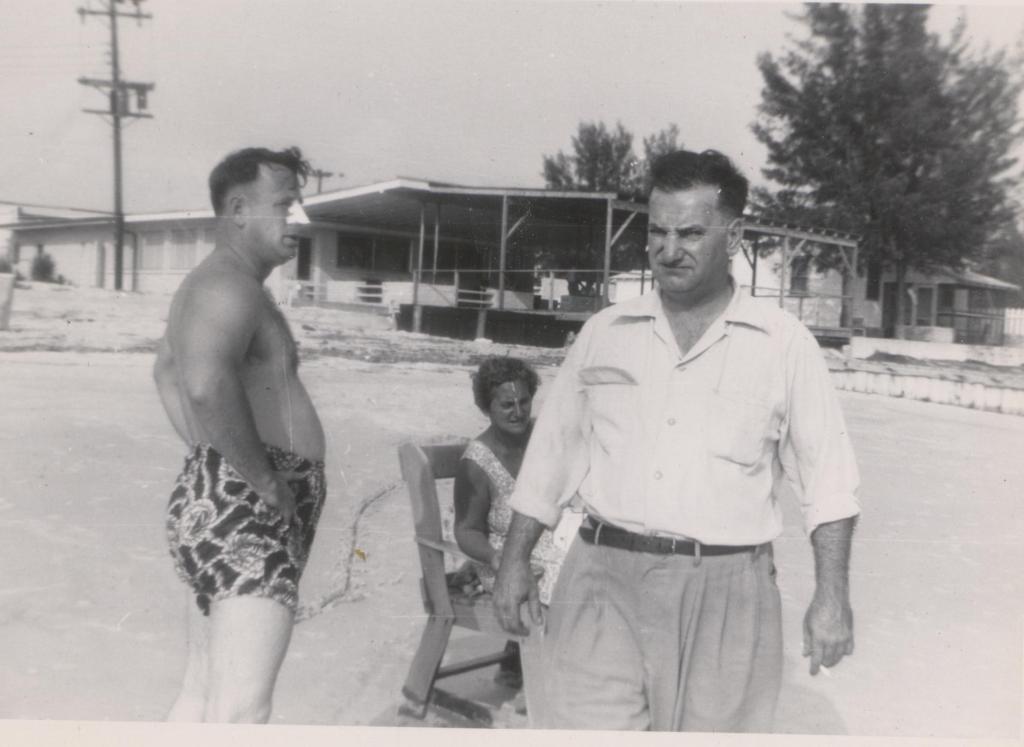

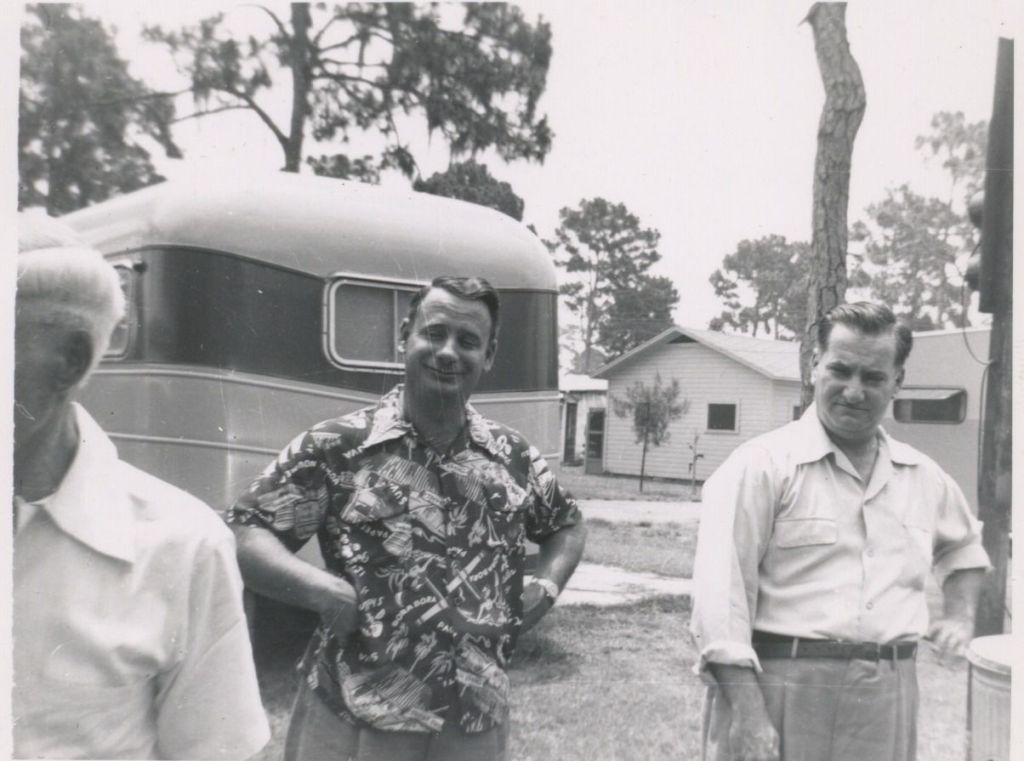

My maternal grandmother, Grandma Bert, was the last of my grandparents to leave us, surviving her first husband, Grandpa Russ1, by 15 years. She lived nearly 92 years, and she spent all of that time furiously pouring her energy into loving her family.

What to Call Grandma

Her name was Alberta, and Grandpa would call her “Bert,” a name I knew from watching Mary Poppins. But I don’t remember referring to her by her name when I was growing up, and it never came up until I had kids and had to figure out what to tell them to call my grandparents!

When we were kids, if we were referring to them, we usually called them “Grandma and Grandpa Clark,” to differentiate them from “Grandma and Grandpa Callin,” and addressed them as either Grandma or Grandpa in person. So, when I asked how they wanted to my kids to address them, that was the first time I really saw how uneasy my grandmother was with her own name.

I think she was aware that everyone talked about “Grandpa Bob” and “Grandpa Nancy,” and “Grandpa Russ” seemed to work for him, but Grandma was in a quandary. She didn’t seem to dislike the name Alberta, but she behaved as though it felt too formal for her warm and bubbly personality. She didn’t seem to mind when Grandpa called her “Bert,” but that seemed too familiar – and I heard her say once or twice over the years that she didn’t think she “should use a man’s name.”

In the end, everyone close to her called her Mom, Grandma, or (if they weren’t related to her) Alberta, and my kids would call her Grandma Alberta or (maybe if they were talking about her) Grandma Bert.

Aggressive Acts of Service

Grandma was an intense and energetic person, forever busy and focused on others. After she died in 2017, I wrote this about her in “When Grandma Played the Organ“:

It didn’t matter where they were, whether you were in their home or they were in yours; Grandma would be busy. She loved to take care of her family. She was forever bustling around the kitchen, cleaning up, playing with the children, singing – always showing us all how much she loved us through those acts of service.

But also, when I wrote about times that she and Grandpa Russ visited us, in “A Fire in the Desert,” I said this:

None of these visits ever lasted long enough for my sister or me, but Mom and Dad seemed to uncoil a little bit whenever the clouds of dust would follow the caravan du jour down the road toward their next stop – usually my cousin’s house a few miles away. Looking back, I can see how my dad, who was always happiest building and tinkering with his handy projects around the property, might have looked forward to not having his father-in-law offering advice on how to build and tinker better. And since they were mom’s parents, I could see how maybe there were lingering childhood issues that every family has that made her feel progressively less in control of her own home until the visits were over.

Whenever Grandma was there, she did everything she could to help. She would dive into meal preparation or cleaning, always bustling ahead of mom or following behind and re-cleaning or “fixing” things – sometimes going overboard in her effort to help out. This would wear on mom’s nerves, but if she said anything about feeling pushed out of her kitchen or pointed out that coming in and “cleaning” the house she had just cleaned felt like criticism, Grandma would be hurt. “I’m only trying to help!”

Now that I’m older and I’ve seen other families with a similar dynamic, I can understand what was going on. Mom was proud of her home and worked hard to keep it orderly. Grandma wanted so badly to show everyone how much she loved them, she couldn’t help sending the wrong message.

I know they talked about it and worked on being gracious with each other, but every now and then, Mom might have to gently convince Grandma to just relax and visit with us. But a lifetime of energetic service to others meant that she was not in the habit!

Life After Grandpa

Grandma outlived Grandpa Russ by 15 years, and I know how lonely she was without him. I don’t remember much about those years, because I was busy moving my family across the country to Maryland, and once I got settled there, I often worked 14 hour days in addition to an hour-long commute. But I remember what Grandma said when she called me to tell me her good news.

She had met a man at her church, Sherwin, and he had proposed. Once I congratulated her, and told her how happy I was for her, she joked, “We had to get married, you know!” She thought that was pretty funny, given that she was 79 years old and had a hysterectomy when she was in her fifties. I’m pretty sure she used that line on everyone in the family, and probably at the wedding. (In case anyone wondered how I acquired my sense of humor, I’m descended from four hilarious, and sometimes surprisingly inappropriate grandparents!)

When Sherwin died in 2008, they had only been together for about four years, but he left her a nice house in Sun City and enough of a nest egg to keep her comfortable and independent. Once again, she struggled to stay busy and keep the loneliness at bay. I know she went through a rough time when her older sister, Lyle, died in 2011. They had lived 2,000 miles apart for more than 50 years, but she told me that loss was the one that made her feel like the only one of her generation left.

But in her last couple of years, Grandma managed to find more friends at her church and stayed more engaged. She even met and married Jack, a preacher who reminded her a little bit of Grandpa, with big dreams to save the desert Southwest.

In the end, Grandma did stay with us longer than the rest of her generation. She loved us all as vigorously as she could for as long as she could, and we were lucky to have had her in our lives.

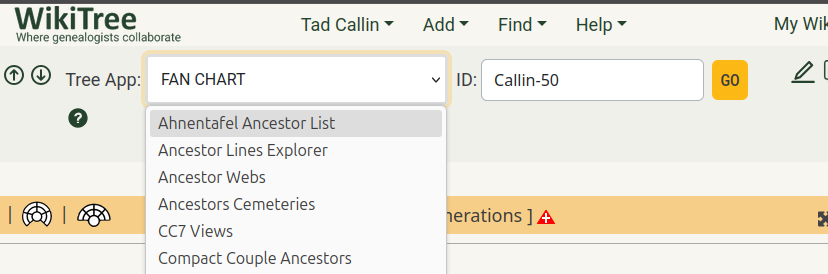

- See Ahnentafel #10 from last week. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.