Teasing meaning from the absence of evidence (part 3)

Previously, in Still Finding James Callin, we looked at the Revolutionary War muster rolls, examining whatever they could tell us about him, and we talked about how they loosely support the statements made in George W. Callin’s 1911 Callin Family History.

James, last noted in the 4th Virginia Regiment rolls as “supposed to be with Genl. Scott,” is effectively missing from the records where we would expect to find him after December 1779. Today’s post is meant to provide some historical context and explain why I think the James Callin listed in a 1794 Kentucky Militia record might be the same James Callin we saw in the Revolutionary War.

Thanks again to my cousin, Joan (Callin) Foster, who dug up a lot of these records. If you happen to study this period and have any comments, they would be most welcome.

And if you want to follow future updates, be sure to subscribe!

Private Callin and General Scott

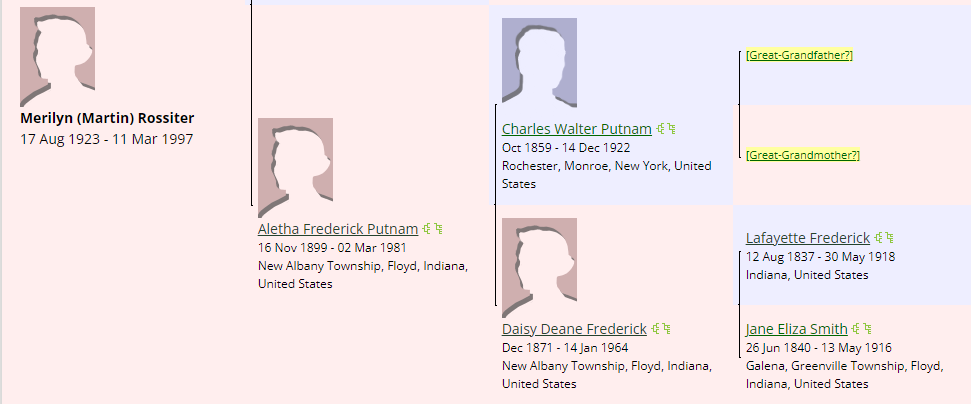

Referring to the 1777-1779 4th Virginia muster rolls, we can state with high confidence that James Callin served under General Charles Scott during the Battle of Germantown and was present during the winter encampment at Valley Forge. After the Battle of Monmouth, on 14 August 1778, Scott was given command of a new light infantry corps organized by Washington, and he also served as Washington’s chief of intelligence.

There is no reason to believe that James was part of Scott’s light infantry or intelligence operation. His muster records include September 1778 notations that suggest that James was injured or sick. The muster roll for September 1778 is dated 5 October and names his location as “Hosp. Robinson’s house” – most likely referring to the home of loyalist Beverley Robinson, which had been confiscated by the Continental Army and was used by both General Benedict Arnold and George Washington.

We discussed before that the rolls show James Callin on furlough from December 1778 through March 1779, and that may have been when he was married. Coincidentally, Gen. Scott was furloughed in November 1778, until Gen. Washington sent him a letter in March 1779 that ordered him to recruit volunteers in Virginia and join Washington at Middlebrook on 1 May 1779.

The muster roll for March 1779 places the 4th VA in Middlebrook, and the payroll for that month shows James as “On furlough Va.” instead of simply “on furlough” as he had been listed for the preceding months. In May and June, his records state that he went on furlough on 15 April, and beginning in July, the rolls indicate that he is supposed to be with Gen. Scott in Virginia. This suggests to me that James Callin was among the Virginians Scott recruited to his new units during this time frame.

Several conflicting orders were issued during the fall of 1779, as reports that reached Gen. Washington about British plans led him to shift troops to South Carolina. Gen. Scott forwarded most of the men he had been recruiting to join Benjamin Lincoln’s force near Charleston.

James Callin’s last appearances in the 4th VA rolls suggest he remained with Gen. Scott in Virginia until at least November 1779. After 9 December 1779, there are no more records that name him. Congress and Washington decided to send the entire line of Virginia Continental regiments (almost 2,500 men) to join Lincoln’s army that December.1 We can only guess whether James was among them.

The Siege of Charleston

Scott arrived in Charleston on 30 March 1780, as British General Clinton laid siege to the city. The Virginian reinforcements arrived on 7 April. All were captured when the city surrendered on May 12, 1780, and Scott was held as a prisoner of war at Haddrell’s Point near Charleston.

Assuming James Callin was among the 750 common soldiers who had made the 4-month, 800-mile march from Morristown, New Jersey, to Charleston, he may have been among those captured. He would probably have been considered a Continental soldier at that point.2

While militia troops were released on parole (promise not to take up arms again unless exchanged), the 2500 Continental soldiers from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were marched into the American barracks as prisoners of war. They were allowed to walk about town, however, and about 500 of the American POWs escaped. The British were so offended by this perceived breach of the terms of capitulation that in September they transferred many of the prisoners into the holds of six prison ships in Charleston Harbor – the Esk, Fidelity, King George, Success-Increase, Concord, and Two Sisters. Joining them were Maryland and Delaware Continentals captured at the Battle of Camden on 16 August 1780.3

If James was one of the 2500 soldiers captured as a prisoner of war, there is a 20% chance he was one of the 500 who escaped. The remaining prisoners were sent to the prison ships in September 1780 – which is also the month in which James Callin’s original enlistment would have expired. One explanation for not seeing him in the records could be that when he escaped, he returned home (remember, a 4-month journey down) only to be discharged at the end of his enlistment. Or…

Remember last week, in Edward’s Trail, we discussed how Edward Callin – who enlisted at the same time as James – may have been involved in the Jan 1781 mutiny of men held after their enlistment expired. If James, an escaped POW, took 4 months to return north, he would have arrived in the aftermath of that mutiny. Or…

In July 1781, nearly all American prisoners of war in the South were released as part of a prisoner exchange between the United States and Britain.4 If James had been on the prison ships, he would have been returned home after his release, and his enlistment would have already been up.

We don’t know where James was after Dec 1779, whether he went to Charleston, whether he was captured, whether he escaped, or whether he ended up on a prison ship – but we have to assume that he survived whatever adventures he was involved with, otherwise, that information would have surely found its way into the Callin Family History. The Callin Family History asserts that James served until the war’s end, and then settled on federal land in Westmoreland County, but as we mentioned in a previous post, no such land records have been found.

That said, let’s continue to look at General Scott’s story and explore that 1794 clue.

The Story of General Scott

Scott was paroled due to ill health on 30 January 1781, and after he was exchanged for a British officer in July 1782, he was put back on duty to recruit in Virginia again. Recruiting stopped when the preliminary peace agreements between the United States and Great Britain were signed in March 1783. Scott was made a major general on 30 September 1783, just before his discharge from the Continental Army.

Scott first visited Kentucky in 1785 and settled near the city of Versailles in 1787. The new United States had a much worse relationship than the British had with the Native American tribes that lived throughout the Northwest Territory. In July 1787 Scott’s son, Samuel, was killed and scalped by Shawnee warriors as he crossed the Ohio River in a canoe – while Gen. Scott watched helplessly from the shore.

Tensions built in the region until Washington authorized a campaign against the tribes living around what is now Fort Wayne, Indiana, led by General Josiah Harmar. (Harmar had been the lieutenant colonel in command of the 6th Pennsylvania Regiment during the Revolutionary War, the unit Edward Callin likely transferred to in 1778.)

1,500 settlers were killed between 1784 and 1789, as more encroached on territory along the Ohio River. Gen. Scott raised a contingent of volunteers to follow Harmar in April 1790 that ultimately caught and killed four Shawnee but didn’t accomplish much else. Harmar’s Campaign in October of that year was considered a disaster, demonstrating that the Kentucky militias were reluctant to serve under federal command.

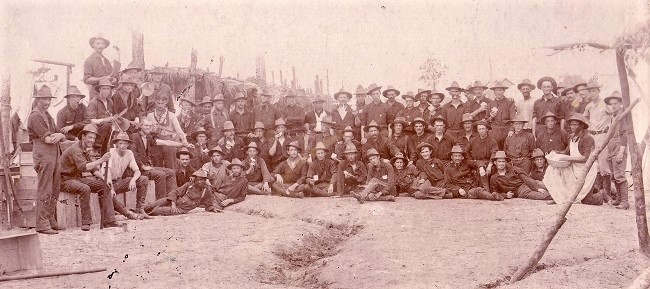

Congress approved a 5,000-man federal force in March 1792, and for two years, federally authorized troops under General Anthony Wayne tried to work with the two new Kentucky militia Divisions commanded by General Scott and General Benjamin Logan. After earning the grudging respect of Kentucky soldiers, Wayne led a combined force supported by Scott’s Kentucky militia in the Battle of Fallen Timbers on 20 August 1794. The battle took place near modern Maumee, Ohio, and led to the Treaty of Greenville a year later.

Among Scott’s troops that summer, a single record shows us a familiar name – two, actually:

Muster Roll of a Company of Mounted Spies and Guides under the command of Captain Joshua Baker, Major Notley Conn’s Battalion, in the Service of the United States, Commanded by Major General Charles Scott, from Jul 10 to Oct 21, 17945

Rank, Name:

[Private], Callen, James

[Private], Callen, John

Conclusion:

This is a very thin peg to hang such a bold claim, but I think the James and John Callen named in that Kentucky Militia record could be the brothers named in George Callin’s Callin Family History. It’s not much of a stretch to guess that James Callin’s “Westmoreland County” land might have been in modern-day Virginia, or that he sold it to move to Kentucky. And if he lived in Kentucky, he would have been a good candidate for service under his old commander.

Serving in this unit would have also taken James and John all over what is now the state of Ohio. The site of the Battle of Fallen Timbers is only 100 miles from the township that James’s sons (also named James and John) would settle on 15 or 20 years later.

I have to wonder (since I still don’t know) where James lived after the Revolutionary War, where he raised his family, and where he died. I’ll keep looking, but if anyone thinks they have an answer: Contact Mightier Acorns!

Maloy, Mark, “The Virginians’ 800-Mile March to Save Charleston” – Emerging Revolutionary War Era, 7 Apr 2021.

National Park Service, “Siege of Charleston 1780”

Berry, Mark, “In Enemy Hands,” The College Today, College of Charleston, 25 Jun 2015.

Clark, Murtie Jane, “American Militia in the Frontier Wars, 1790-1796,” pg. 43-44.