What does social media do for you or your research?

This post was intended to be a “here are some social media platforms I’m on and some of the people/groups I follow” post, but I felt like some explanations were needed, and it kind of ballooned into … this. If you already know or don’t care to know what a mess the social media environment is in, and you just want to see my links to other platforms, skip down to “Some Other Platforms.”

The Backstory

For a while, from about 2008 to 2012, I taught a class on “virtual collaboration” to federal employees. After the 9/11 Commission Report was released in 2004, the ODNI (Office of the Director of National Intelligence) pushed to make it easier for the military and intelligence agencies to share information. This was a hard cultural problem because decades of tradecraft were built around compartmentalizing and protecting information so that “the adversary” could not use it against the U.S. Part of the solution was to allow organizations to create tools and platforms on their internal that mimicked the features of various successful social media platforms on the open internet.

My favorite tool was Intellipedia, built using the open-source Wiki Markup software that powers Wikipedia. There were also attempts to recreate platforms to provide the features of Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and more specialized services for things like social bookmarking. But like their Internet counterparts, none of these tools had any value without users. That’s where my class came in.

Teaching this course was a challenge for several reasons. For one thing, people with careers in the intelligence community tended to avoid social media, so we had to teach them about the social media environment “in the real world,” sell them on the idea of being social in a professional way, and then show them how a one-to-many communication tool like Facebook would be more helpful to them than email.

Every class I taught had at least one crusty old coot sitting in the dead center of the room who would listen with a confused look on their face as I walked them through the benefits of working collaboratively, and they would always wait until everybody else was on the verge of accepting the new way of thinking I was offering – and then they would ask:

“But what is this Twitter thing FOR? Who has enough of an ego to think anyone will care what they think?”

What Is It All FOR?

I never did have a good answer to that question. The correct answer is “The platform is FOR you to connect with people who share your interests and coordinate with them to achieve goals you wouldn’t be able to achieve on your own.”

But the last decade has shown us that the owners of the platforms aren’t always interested in your goals.

Facebook has been selling user data, using its algorithm to keep you from seeing what your friends and family post (the people who share your interests), and pushing targeted ads into your feeds, including disinformation from foreign governments seeking to sow chaos and doubt in our population. Twitter is no more, having been purchased by a billionaire who changed its name to “X” and made the platform unusable for anything but political influence.

Back in 2008, when optimism was a realistic view to hold, none of this had happened yet. Not that there weren’t people valiantly warning us that it could happen. People like Cory Doctorow told us early on that we could not and should not trust tech corporations to protect our privacy or our speech – and in 2023, the concept of “enshittification” of social media became more widely understood as people began to catch up to what has been going on for years.

Now we are in a place where people like us – people who want to build a community around a shared interest like Genealogy – have fewer options for doing so. And we have to be more careful about where we invest our efforts so that we are not simply exchanging one bad corporate actor for another.

So What Can We Do?

If you’re reading this, you’re probably already on the Substack platform. Substack (so far) appears to have solved part of the enshittification problem by building itself around a business model that centers us – the users.1

Conventional wisdom tells us “If you are not paying for a service, then you are the product.” We’ve seen how that played out with Facebook and X-Twitter; and for the time being, Substack seems to derive its income from taking a cut of the contributions that readers can pay to writers. This is good, in that the corporation’s motivation is to increase the number of readers, and thus the amount being paid to writers/creators.

Substack’s main purpose is to give a platform to newsletters and podcasts, but they also offer Notes as a Twitter-like tool for spreading awareness and fostering discussions. The algorithm there still seems to be tailored to pushing things that Substack wants you to see to the top of your Notes feed – instead of giving you the option to see newer posts from your friends, first.

Even if you like and trust Substack right now, it is probably a good idea to diversify – if you have a presence on more than one platform, you are more likely to attract an audience from there to your Substack or to find your way to communities or content creators that are not on Substack.

Some Other Platforms – and who to follow there

Bluesky – I am @tadmaster.bsky.social I don’t post much, and when I do, I usually re-post things I like or promote my Substack writing. If you’re looking for interesting people to follow there, click here to see the list of who I follow. They tend to be people from three main circles:

writers and podcasters associated with my work as an associate editor for Pseudopod

Genealogical societies and enthusiasts

music people

Reddit – I am u/Tadmister, but Reddit is more about following communities than individuals. I belong to several fan-based communities built around sci-fi franchises and musicians. To get an idea of what to expect, dip your toe into:

Mastodon – this one is a little tougher to get into – but for the genealogy community, there are a few different servers you can join. I am @mightieracorns@genealysis.social

I use the Tusky Android app to access and post, but I haven’t found Mastodon to be as easy to work with as Bluesky, Notes, or even Facebook.

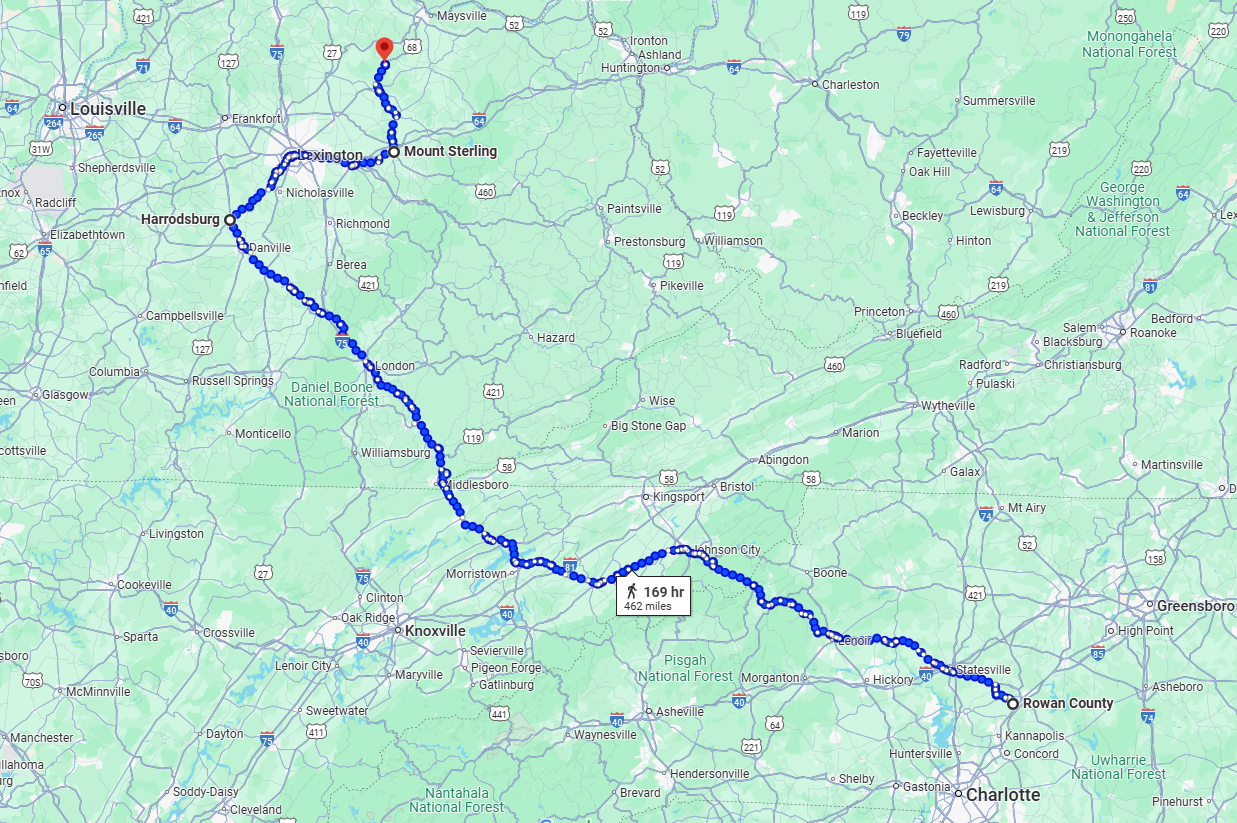

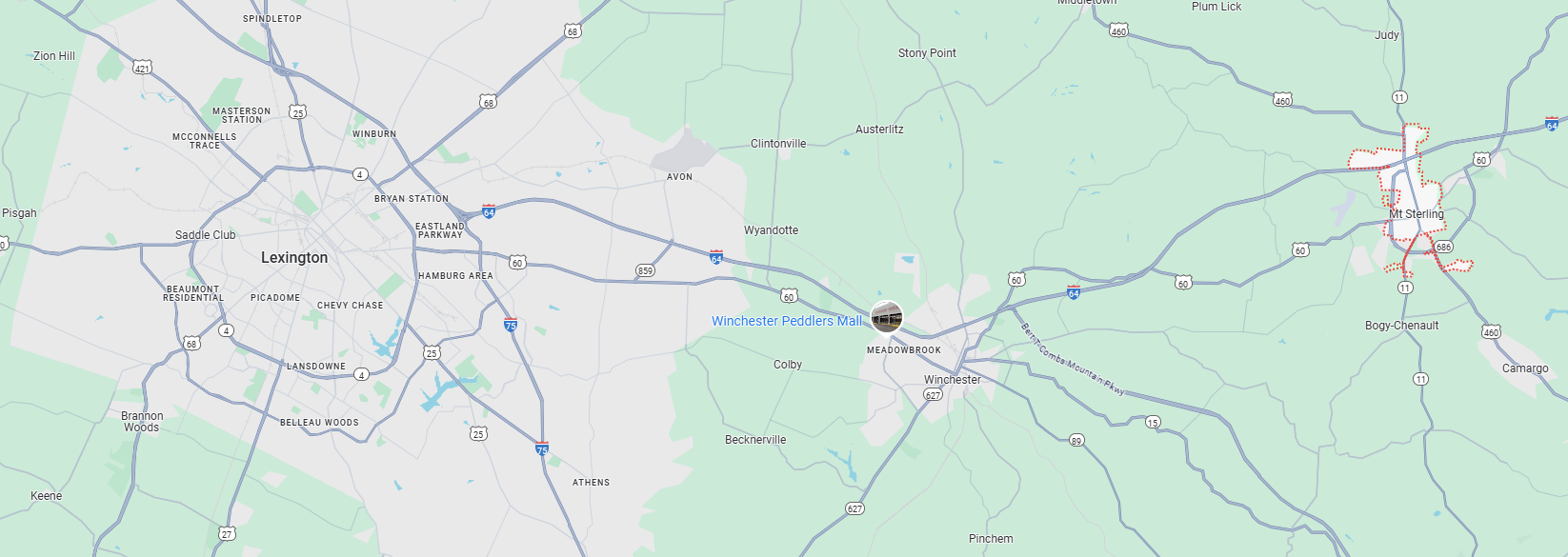

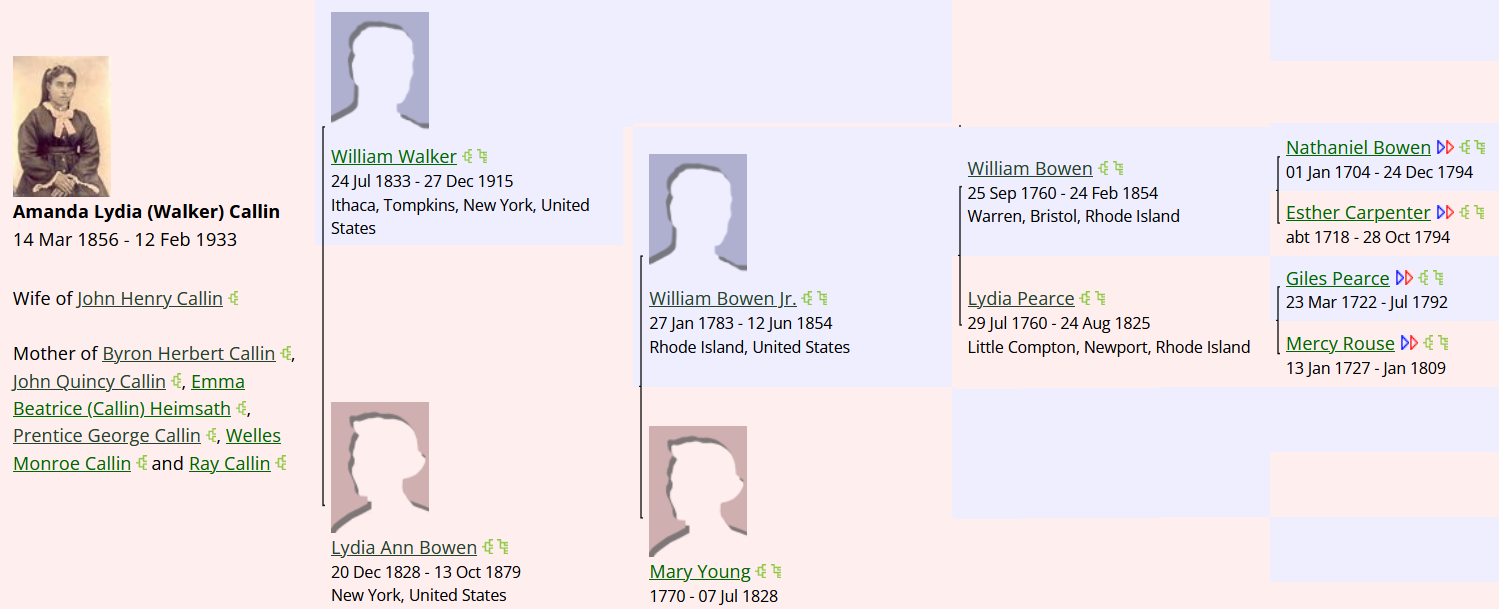

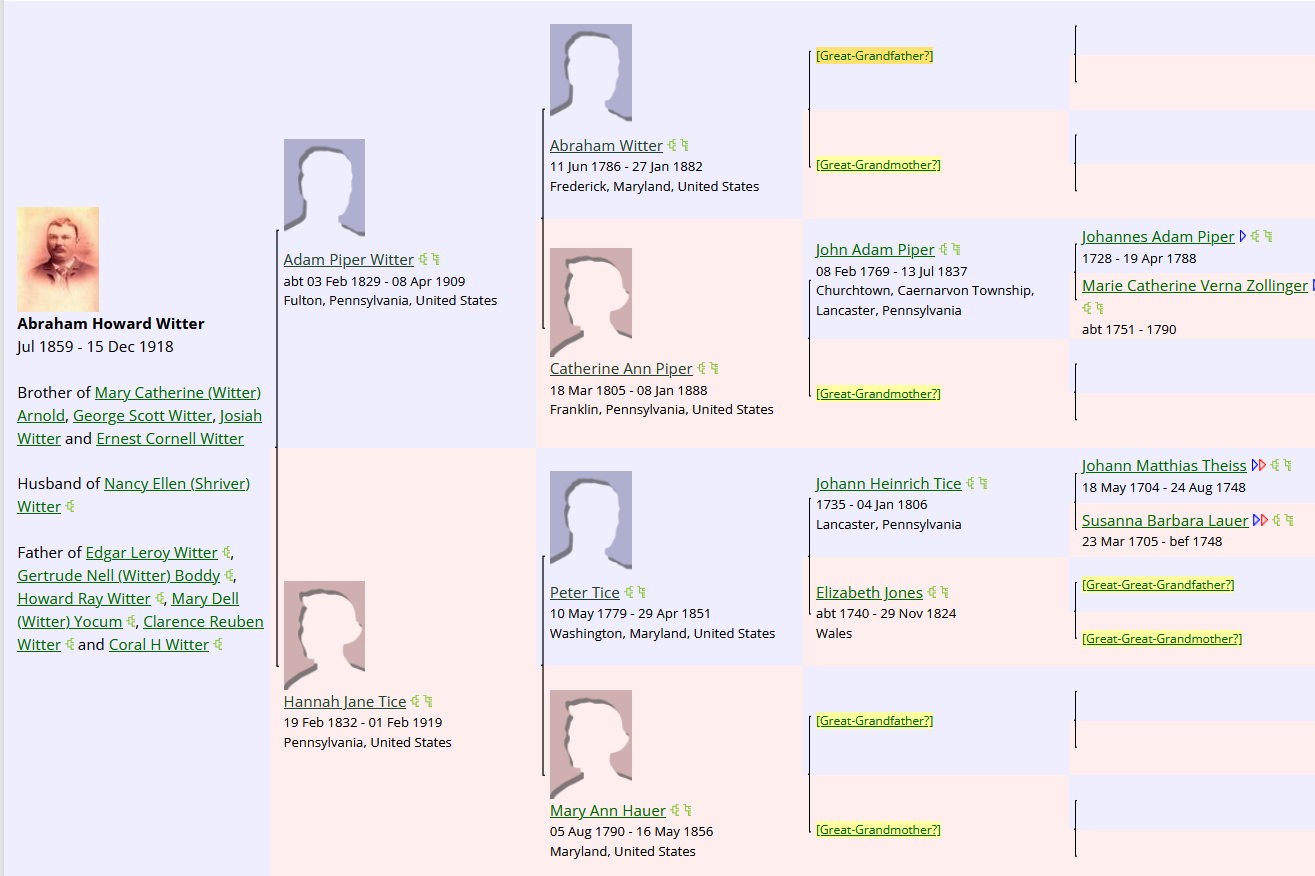

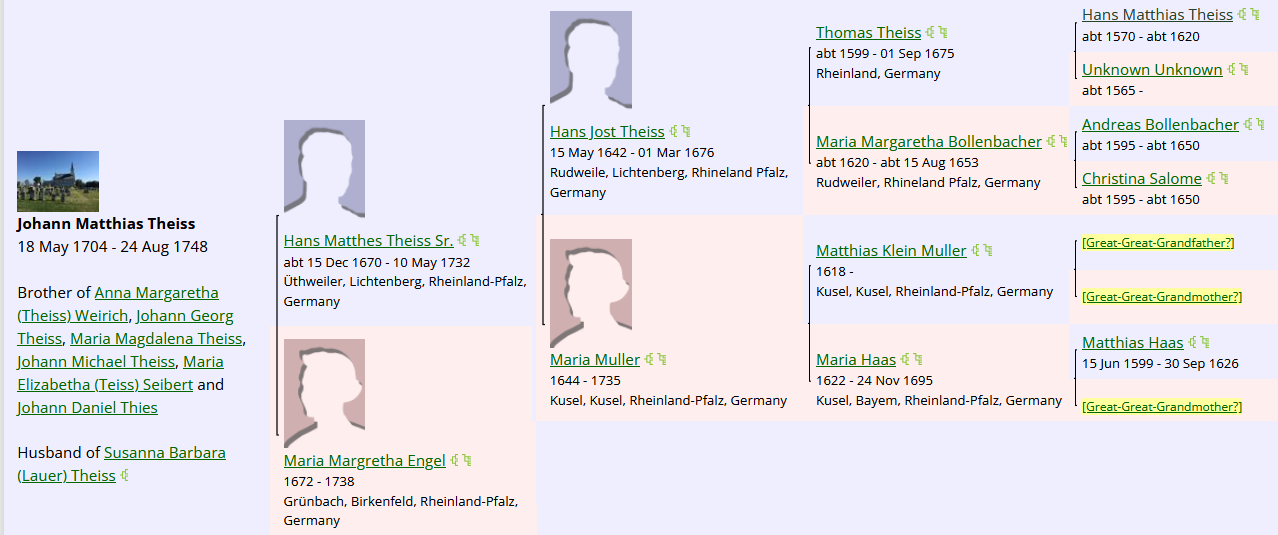

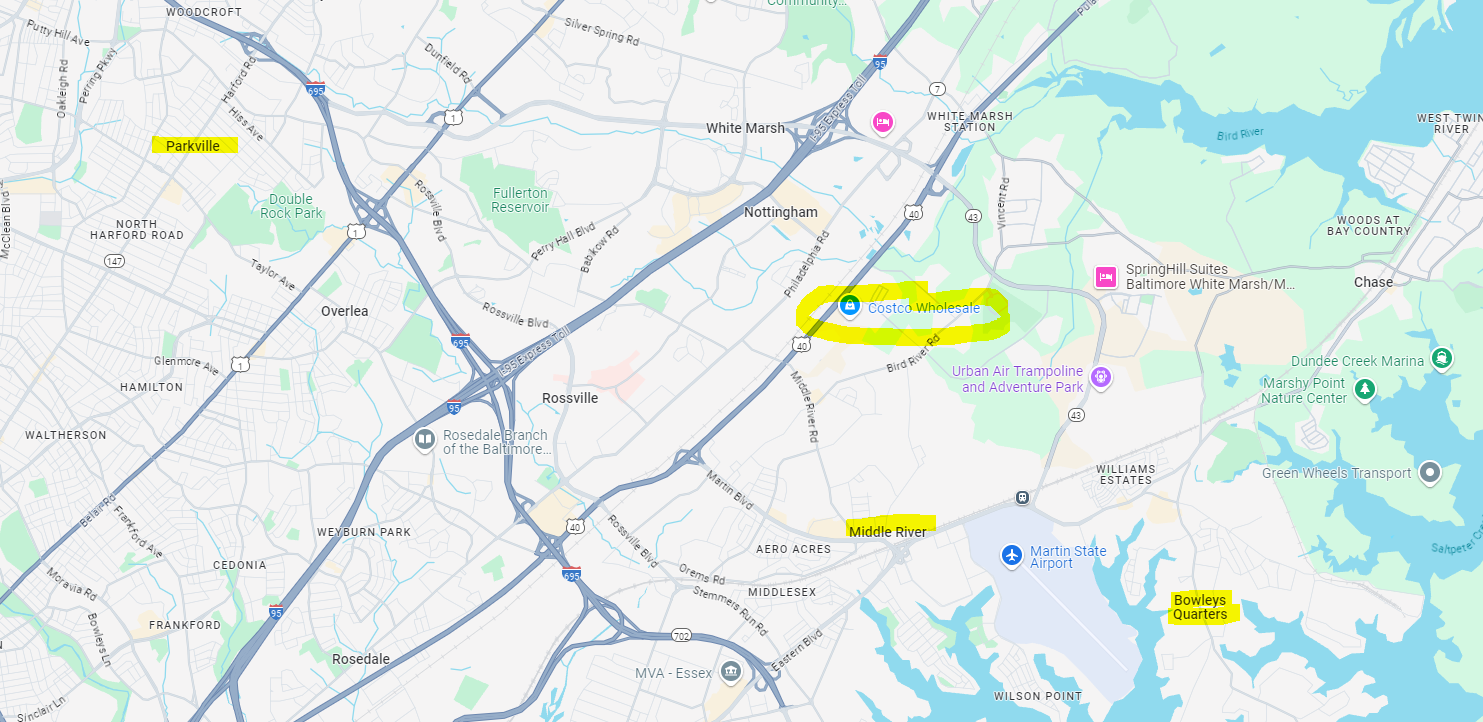

WikiTree – yes, wikis count as social media! If you sign up for a WikiTree account, look for me at Callin-50; you can use their Connection finder to calculate how closely we might be related.

Wikipedia – the granddaddy of the wikis. I have not actively edited in quite a while, but I am still there as User:PapaSmirk, and I have been a financial supporter for many years.

Do you have a favorite?

Who/What to Avoid

Meta (aka Facebook, Instagram, Threads) – I’m still on Facebook, and I try to maintain the Mightier Acorns page there, along with a couple of private groups (that don’t have any activity). If I recognize your name, I might accept a friend request – but they have been swamped with bots and fake accounts lately, so I might not see your friend request or might not know if I can trust it. I have an old Instagram that I ignore, and won’t touch Threads or any of their new products on principle.

X (formerly Twitter) – the biggest and most notorious flame-out in the history of social media. Elon Musk famously purchased the platform, fired anyone capable of making it function, and turned it into an attack vector for cyber-bullies and foreign political influence. If you find either of my accounts there, @tadmaster or @mightieracorns don’t expect much interaction. I keep them alive only to prevent someone from stealing my identity.

Some platforms are purpose-built to advance ideologies or specific communities that I wouldn’t be welcome in or that I would avoid on principle. There are dozens of these.

For example, “Truth Social” was created to give a former U.S. president (and now president-elect) his own platform after he was kicked off of social media for organizing a coup. If you are sympathetic to him, politically, or to his principles2, you might be tempted to join that platform – but you should be aware that its “free speech” ethos is a cover for launching scams and cybercrime activities aimed at its users.

Whatever platform(s) you decide to use, do your homework first, be careful with your personal identifying information, and protect your wallet.

We should all remain skeptical of corporate motivations; if their business model changes, or if they are bought by a larger media company, we could end up back in a Facebook-like situation.

If you are sympathetic to him, you probably won’t be happy with much of what I have to say about him. The actual truth hurts.