Crestline School Dist. No. 78, 1921-2023

I only know the beginning and ending of this story. In between are a century’s worth of individual tales of growth, learning, and the childhood memories of an unknowable number of children.

The first time I learned about the existence of the Crestline School was when another researcher called Seth sent a message through the WikiTree profile of Albert Callin, saying:

Albert designed the District 78 school, which was built in 1921 in the tiny town of Crestline, KS. It can be seen on streetview at the intersection of US 400 and Wyandotte. It was demolished in 2023.

This led me to a site called Abandoned Kansas with an article about Crestline School Dist. No. 78, which includes a photo of one side of the building’s cornerstone (just not the side with Albert’s name on it).

Fortunately, Seth kindly grabbed a photo of his own and let us share it:

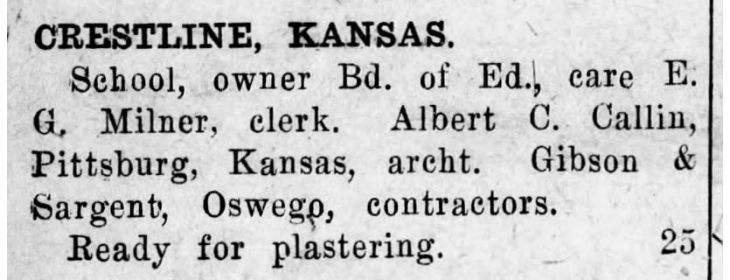

Some minimal digging brought me to newspaper items from 2 July 1921 that helps confirm Albert’s involvement in the building of the school:

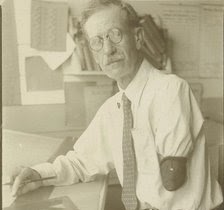

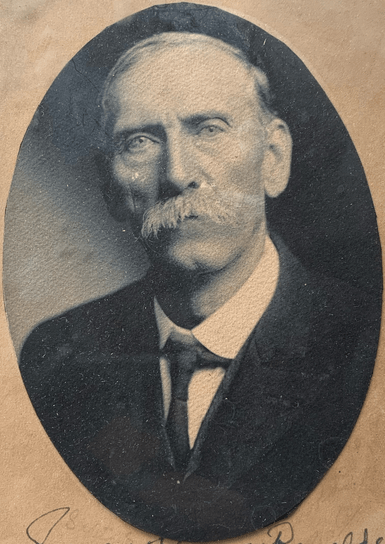

All About Albert Callin

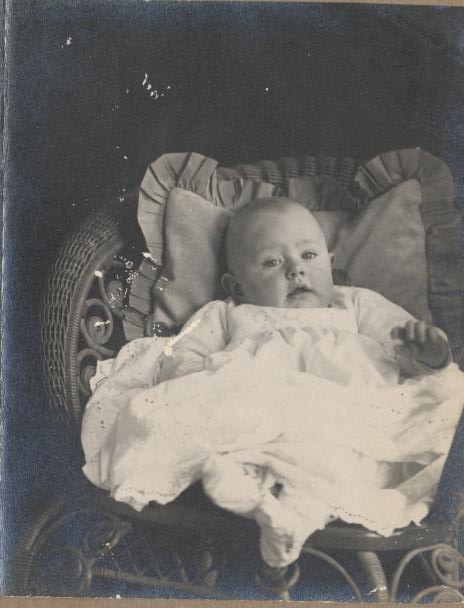

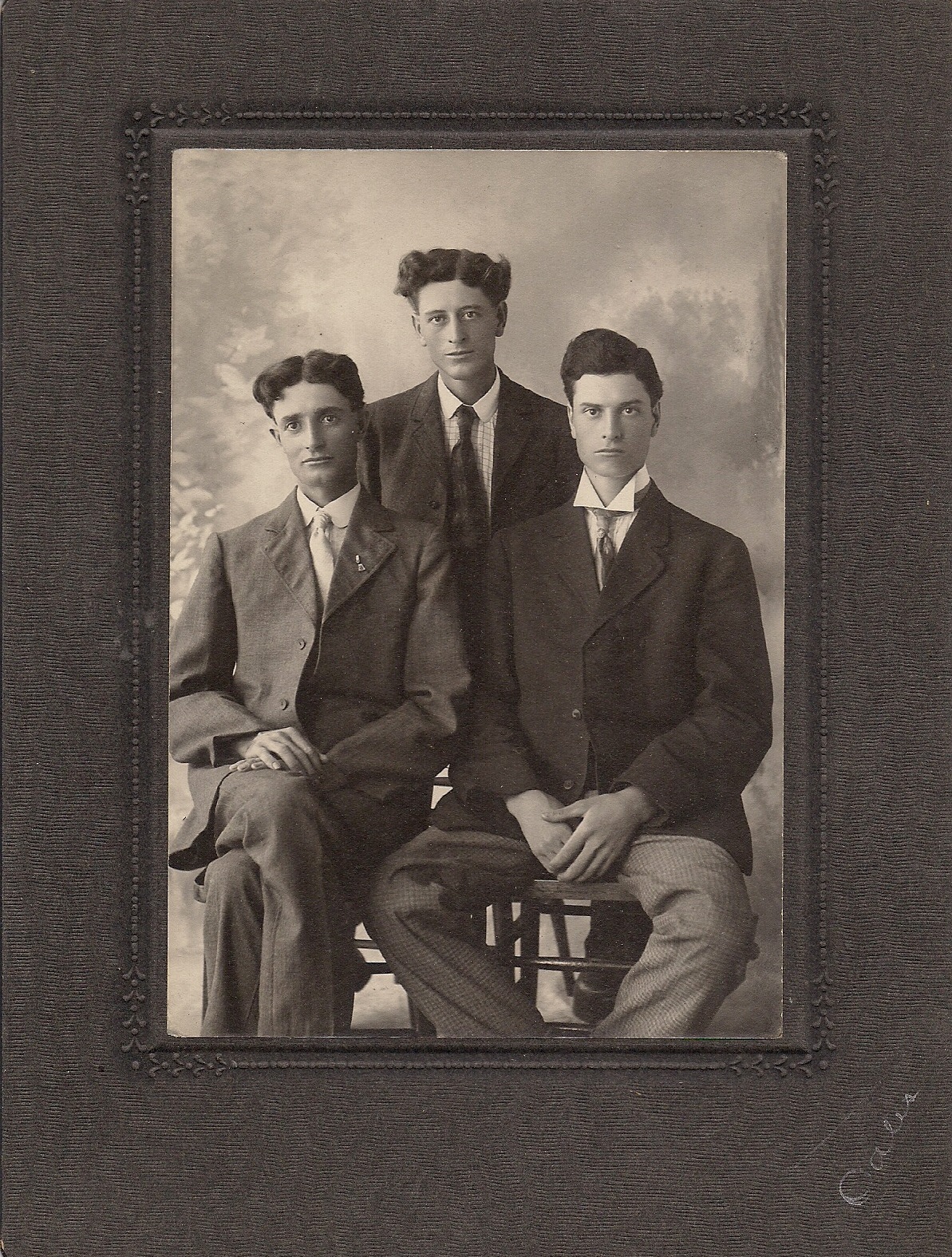

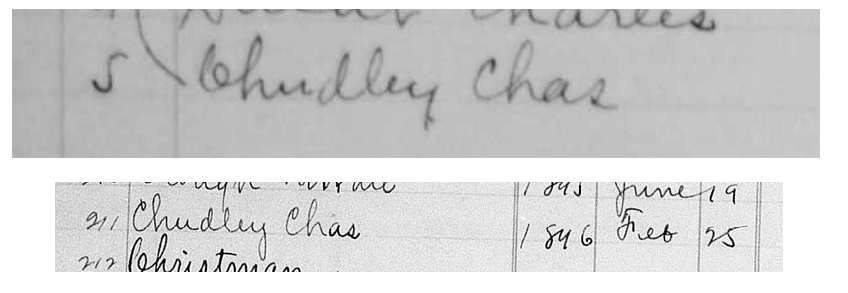

Albert Clifford Callin was the son of James Monroe Callin (1844-1901) and Rosalina Bedora Davenport (1848-1876), the oldest brother of Jessie Chudley (if you recall our earlier post about her mysterious life).

By 1921, the Albert Callin family had been through some dark times. Twenty years before he designed the Crestline school, Albert’s business partner in Toledo had embezzled their investors’ money and left town. Albert insisted on paying back every penny stolen by the partner, and took his family south to Galveston, Texas, where a 1903 hurricane had devastated the town and created a need for builders like Albert.

While working his way to Galveston, Albert took on a number of small jobs to pay his way. On one occasion, he undertook to repair a cotton gin that had jammed or broken. While he was working, someone accidentally turned it on, catching his left arm. He remained conscious and directed his own extraction from the gin. However, the doctors were unable to save the mangled, filthy arm, and it was amputated above the elbow.

The family still made a living in Victoria, Texas, until 1914, when flooding there claimed the life of their 10-year-old son, John Albert, and they moved to Pittsburg, Kansas, where Mamie’s half-brother offered them a place to live. This is where Albert re-established himself as an architect.

The End of the Story

We don’t know how long the Crestline School building stood abandoned before it was demolished in 2023. We know it was a one-room schoolhouse, noted as such in this 1921 article about a school contest:

Union school of Crestline – contest winner 24 Feb 1921, Thu Modern Light (Columbus, Kansas) Newspapers.com

Union school of Crestline – contest winner 24 Feb 1921, Thu Modern Light (Columbus, Kansas) Newspapers.com

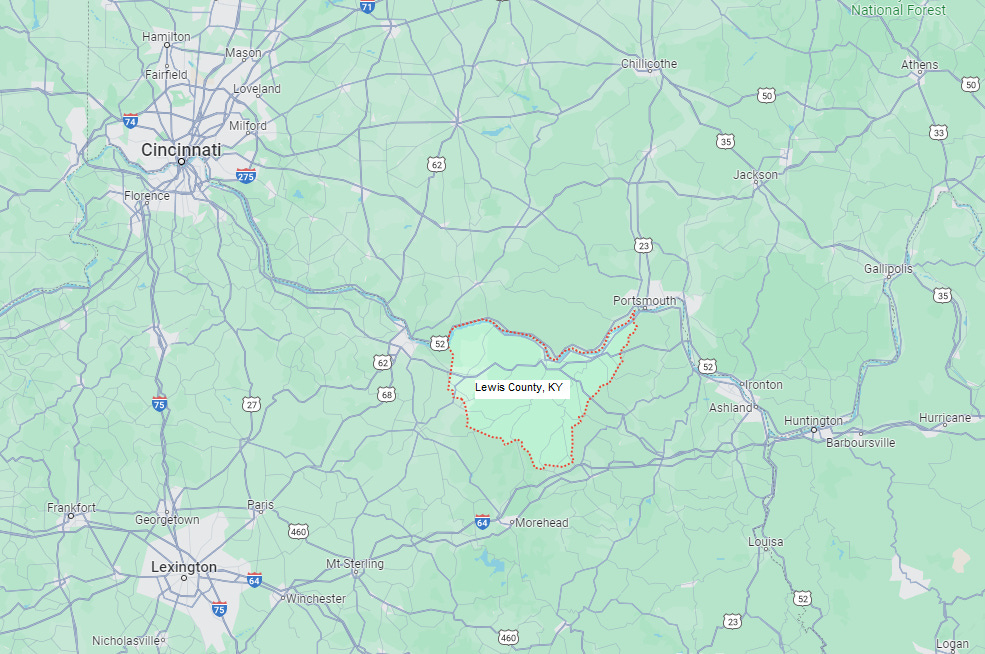

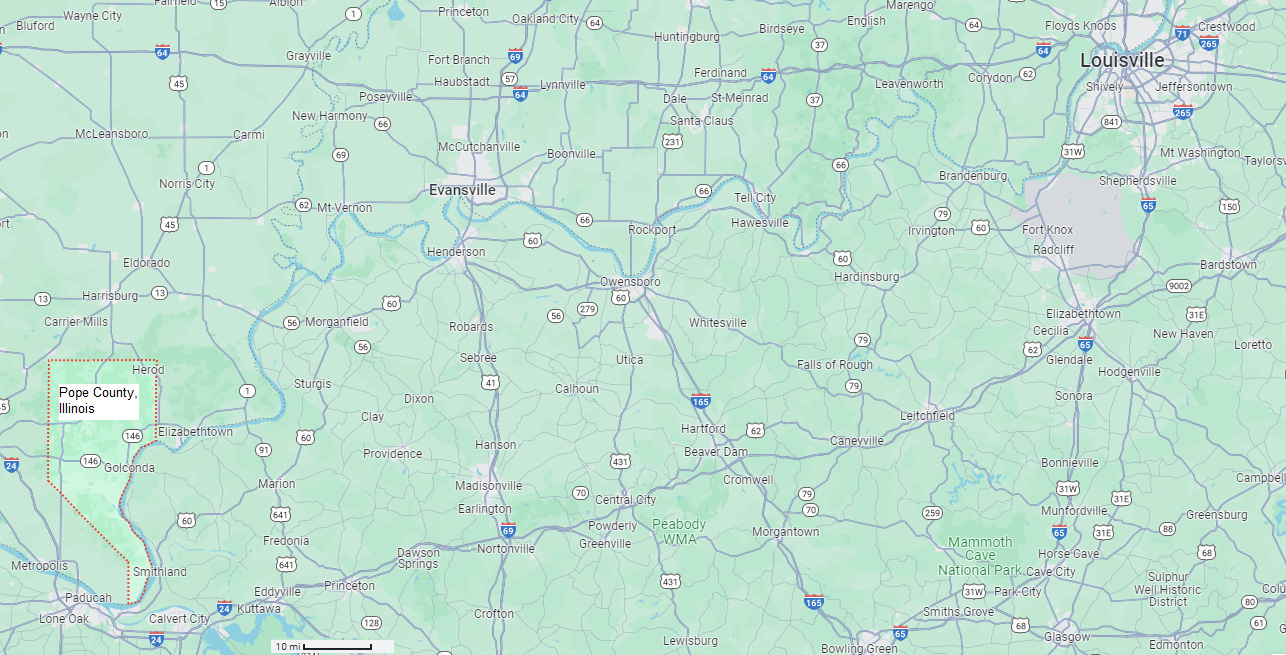

The town of Crestline lies in Shawnee Township, Cherokee County. The school district there was No. 78, and they boasted two high schools as of 1904.1 The one-room Crestline school would have served as a primary school feeding into the high schools. The most recent reference to the school I could find was from a 1931 wedding announcement:

Article from Oct 9, 1931 The Galena Journal (Galena, Kansas) Marriage <!— –>https://www.newspapers.com/nextstatic/embed.js

In general, one-room schoolhouses were phased out during the 1940s and 1950s in favor of larger, more centralized schools. Given the devastation of the Great Depression on rural areas throughout the Midwest, it’s possible that the Crestline building stood unused for as long as 90 years, if it closed down in the mid-1930s.

We do know that Albert and Mamie Callin retired to Greenwood, Colorado, around 1929. They died in the early 1930s and were buried in New Hope Cemetery in Fremont County, Colorado. It’s possible that one of the buildings Albert designed is still standing somewhere, but we know the Crestline school is not one of them.

Perhaps with more digging, we’ll find a survivor one day.

- Allison, Nathaniel Thompson, ed, History of Cherokee County, Kansas and representative citizens, Biographical Publishing Co., Chicago, Ill., 1904; page 84. ↩︎

–>

–>

You must be logged in to post a comment.