Since April, I have been sending out snapshots and overviews of the families that once lived in Milton Township, Ohio. Before we get into the last of the Callin families that moved away in the 1840s, let’s review the timeline.

If my suspicions about James Callin, the veteran of the Revolutionary War, are correct, he was part of the Kentucky Mounted Cavalry that participated in the Northwest Indian War, a military campaign against a Confederacy led by the Wyandot people, who were trying to keep Americans from settling the region north of the Ohio River valley. James and John Callin were listed as privates “under the command of Captain Joshua Baker, Major Notley Conn’s Battalion, in the Service of the United States, Commanded by Major General Charles Scott, from Jul 10 to Oct 21, 1794” – and almost certainly fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, which took place at the site of the present-day city of Maumee, Ohio.

- Based on the earliest record I have that might show our James Callin, he was at least 21 years old and paying taxes in Hempfield, Pennsylvania, in 1773.

- Based on the furlough recorded in the 4th Virginia Regiment’s muster rolls, he may have gone home to be married in late 1778/early 1779; I estimate that his son, James “2nd”, was born at that time.

- After the Revolutionary War ended in September 1783, James took his family and “settled on government land in Westmoreland Co. in Western Penn., where they remained the remainder of their lives,” but we don’t have any evidence of this outside of The Callin Family History.

- By 1794, James (age 42), may have been living in Kentucky, or he may have heard that his former commander, Gen. Scott, was recruiting for his militia and came from Westmoreland County to join. It is also worth considering that the James and John Callin we see in the Kentucky militia were his sons, but they would be 15 and 14 years old, at best, and unlikely to be accepted in the militia.

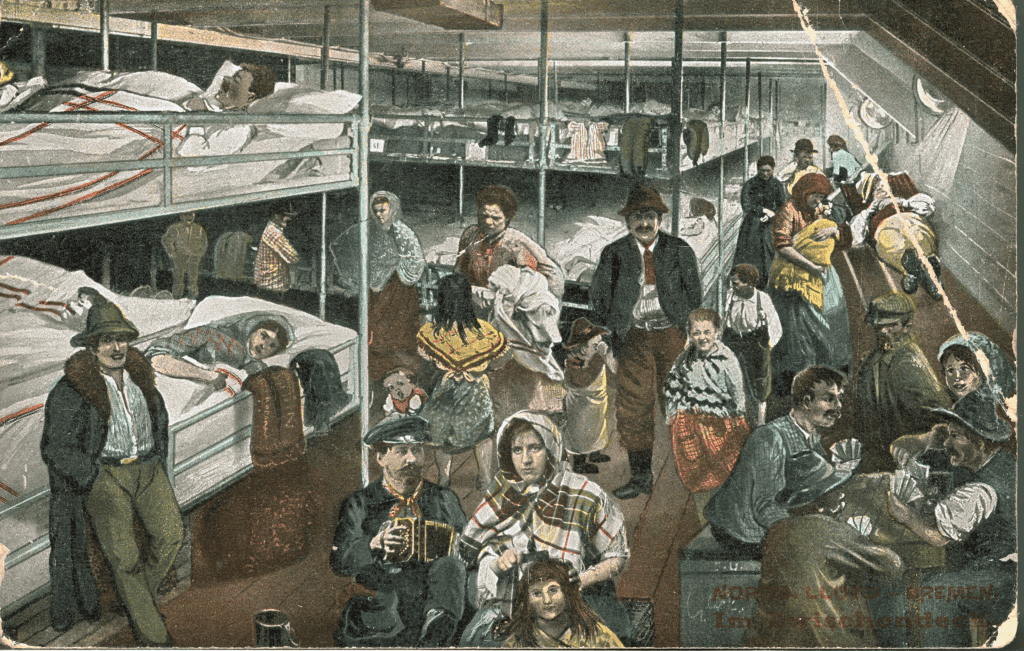

But by 1810, the sons were 31 and 30, and Ohio had been a state for seven years. And as of 1820, our speculation ends and the U.S. Census records the brothers, James and John, in Richland County, on a farm in Milton Township.

The Last to Leave

Elder brother James “2nd” and his wife, “Aunt Mary,” had six children, most of whom were born in Pennsylvania before the family moved to Ohio. Aunt Mary was a founding member of the Hopewell Presbyterian church. In 1820, James was killed by a neighbor.

Their two daughters, Elizabeth and Sarah, married sons of Benjamin Montgomery, and the Montgomery families ended up in Rochester, Indiana. Their three younger sons, Hugh, Alec, and James, left for Iowa, taking Aunt Mary and their wives and children with them. Their wives included another of Benjamin Montgomery’s daughters, who married Hugh, and a cousin, Margaret. Only the elder son, Thomas, stayed in Milton Township.

Younger brother John married Elizabeth Simon in Pennsylvania, and they had six children before moving to join James and Mary on the farm in Ohio in 1816. They had three more children after arriving in Ohio, including Margaret, who would later marry her cousin James and leave for Iowa. Their oldest son, also called John (1802-1825), died at age 23. Ten years later, the senior John Callin died of tuberculosis and was buried in Olivesburg Cemetery.

Six of their surviving children remained in Ohio. The oldest, Sarah, married John Scott and left for Winnebago County, Ilinois. And finally, Eliza Callin married James L. Ferguson.

We don’t actually know when most of these families left Ohio – the scant evidence we have suggests they left within a year or two of 1840. But The Callin Family History says that Eliza and James Ferguson moved to Indiana around 1851, and their two youngest children were John D. Ferguson, born in Ohio in 1848, and Minerva, born in Indiana in 1854.

Since they appear in the 1850 Census in Jackson, De Kalb County, Indiana, I think they must have moved in 1849. By then, Milton Township had also left Richland County. Ashland County was formed out of parts of Richland and neighboring counties, and part Milton Township became what is now Milton Township in Ashland, and part of it became what is now Weller Township in Richland County.

Meet the Fergusons

James Ferguson was a farmer, as you might have come to expect of the men of his generation. We don’t have records to pin down the details of his marriage to Eliza Callin, but their first child was born in 1833.

We also don’t know where they were living between their wedding and their move to Indiana in 1850. There is a James Ferguson listed in 1840 living in Brown township, Delaware county, 133 miles to the west of Milton township; this James Ferguson had children of ages that match our James Ferguson. The important thing for us is that we have them placed in Indiana in 1850.

By 1860, Eliza’s mother, Elizabeth (Simon) Callin, was living in the Ferguson household on James’s forty acre farm near Auburn in De Kalb county. The Callin Family History says that she died in November 1864 and was buried in Auburn. It could be that she moved to Indiana with James and Eliza, or she followed along during the 1850s. She certainly got to spend her last few years with her younger Ferguson grandchildren.

Of the eleven Ferguson children, only George died without leaving behind a family of his own. The Callin Family History says that he was twenty-seven years old when he was “Killed in battle on the Potomac, Feb., 1865.” If our George is the George Ferguson who enlisted in the 13th Regiment of the Indiana Infantry, they would have been some 380 miles south of the Potomac in February 1865, engaged in operations around Wilmington, North Carolina. George may well have enlisted in another state, though, as many young men did if they could not find a regiment in their home state. If that was the case, he might well have been killed on the Potomac.

Eliza died on 17 November 1870, and was buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in Auburn. In 1885, James seems to have grown ill, and he updated his will accordingly (transcribed by me – consider all of the spelling irregularities to be part of the original):

“Know all by these presents that I James L. Fergeson son of Jackson township in DeKalb County State of Indiana being of sound mind and memory do make and publish this my last will and testament, revoking all former wills by me made; that is to say

“First–I give and devise unto Six daughters Mary McNabb, Elizabeth Reed, Mildred Ettinger, Margaret J. Gallaher, Sarah Myers, and Eliza Myers, in equal portion all my household goods of every name and character to be by them divided

“Second–To my Son John D. Furgeson I devIse the entire use and possession of the forty acres of land I own in said township for the term of two years from my death upon the express condition that he pay or cause to be paid all my debts; expenses of my last illness and funeral and the taxes on said land for the two years

“Third–All the balance and residue of my estate real and personal I devise (except as Stated above) unto my three Sons James L Furgeson Jun- Nicholas Perrine Furgeson and John D. Furgeson in equal portions and Shares- provided that they shall and will pay or cause to be paid within three year from my death the sum of Four hundred and twenty (420) dollars – that is to Say – that they Shall pay to each of my above named daughters the Sum of Sixty (60) dollars and to said John D Furgeson who has purchased the interest of Clarissa J Copp daughter of my daughter Minerva Copp deceased in my estate the further Sum of Sixty (60) dollars, Interest is to be charged on said. Four hundred and twenty dollars if not paid within Said three years

“Fourth- I name and advise that my Son John D Furgeson act as the Executor of this will.

“In witness whereof I hereunto Subscribe my name and affix my seal this 12th day of December 1885”

Patterns and Dynasties

Not only did this Ferguson family have a lot of children, ten of those children had families ranging in size from two grandchildren to nine grandchildren – giving Eliza 47 grandchildren.

Eliza’s two eldest daughters married men named McNabb (I haven’t established whether they were related to each other), and two of her younger daughters married brothers named Myers. One of the Myers grandchildren was the grandmother of Wiley Cowan, whom you might remember from previous posts.1

There are so many descendants in that branch of the family, I could probably spend several years posting about one descendant per week. But we all must make choices about where to spend our focus and our resources, so for now, I will let them go and hope that I’ve been able to help some of their living descendants find their way back to Milton Township.

- Wiley was the subject of three 2024 posts, beginning with Unboxing Wiley. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.