They only point the way… the rest is up to us

If you were a fly on the wall… or if I set up a Twitch stream… the scene that would play out in front of you might disrupt your image of the studious researcher.

I know I like to think of myself as a jovial and sedate scholar, calmy reviewing search results and zeroing in on the information that lays out a sensible map of where my ancestors were, what they were doing, and when it all happened.

But then there’s reality.

Reality often involves me, in my pajamas at midday, craving a third cup of coffee and spluttering exasperated questions at my monitor.

“How is he in Iowa? He’s supposed to be in Indiana?” (Frantically rechecking all place names beginning with “I” to make sure I didn’t confuse them.)

“Wait – who is Eunice? I thought he married Elizabeth!!”

“Why were they married in North Carolina??? THEY LIVED IN IOWA! No, wait… INDIANA! Augh!”

Those who practice the art of profanity may insert words beginning with “f” as they see fit. I know I did.

These outbursts were also periodically punctuated by me, raising a fist at the heavens and cursing the patriarchy for effectively erasing women from history at every opportunity.

The Back Story

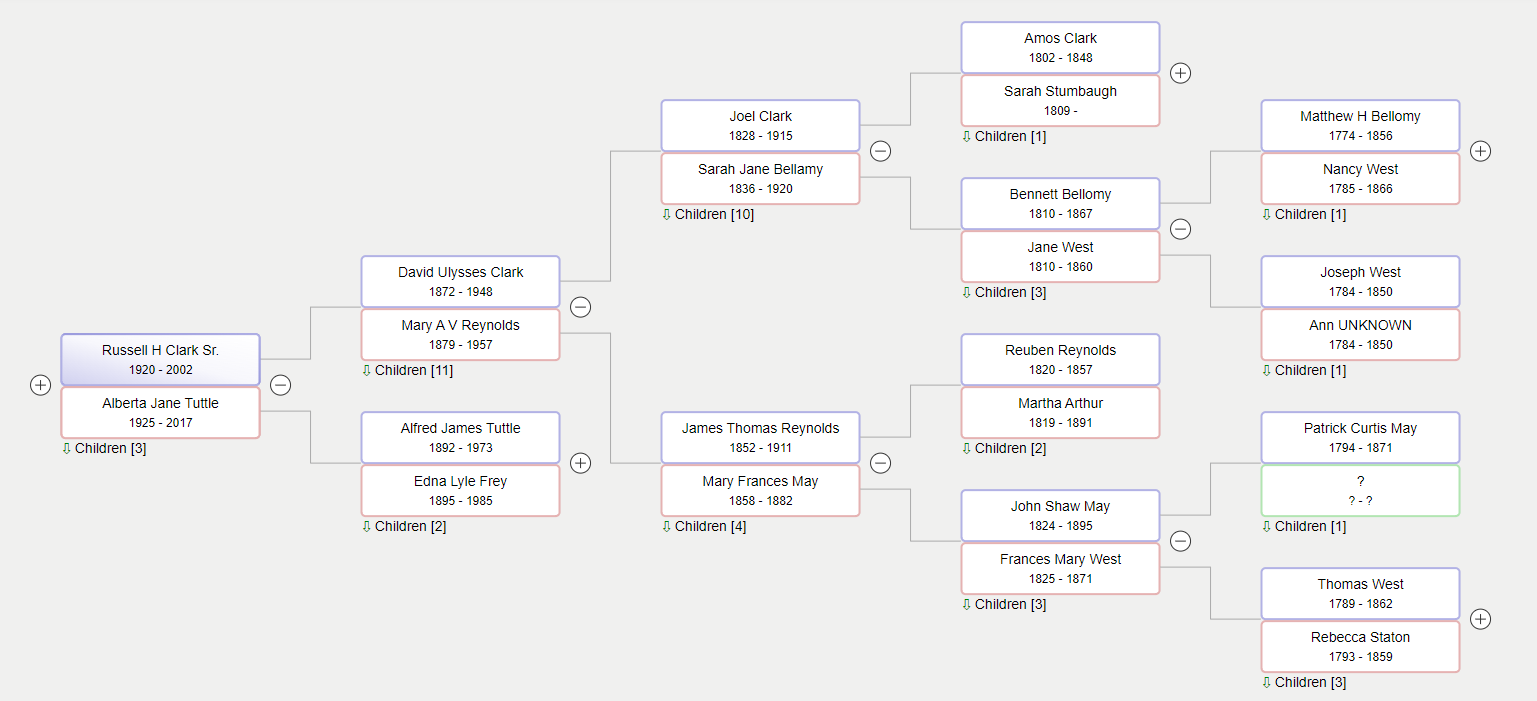

I try to balance the posts you see between my family and my wife’s family. I believe my children (and perhaps, someday, grandchildren) deserve to see their whole family history and not just my half.

So, when I look at my output on Mightier Acorns and see a growing imbalance, I dive back into the story of my in-laws. And the best stories come from asking questions about the gaps and anomalies. Today’s anomalies lie in the ancestry of my wife’s grandmother, June (Shuffler) McCullough.

June’s great-grandfather, Valentine Shuffler, is overdue for an appearance in my Wavetops series, but most of the information about his parents comes from “received wisdom” – online trees and unsourced notes on Ancestry. To tell Valentine’s story, I have to know more about his mother…and anyone who has read Laura Numeroff’s “If You Give A Mouse a Cookie” knows where this story goes.

At any rate, the scene I described above came out of my attempts to trace Valentine’s mother, Ruth Dyer, and her origins.

Quakers On the Move

The Religious Society of Friends kept extensive records of the lives of its members. Ruth Dyer’s parents were Friends – better known by outsiders as “Quakers” – but the Society’s records operate a little differently from the local county vital records I’m familiar with.

For one thing, the Friends were a lot more intrusive than local governments were in the types of things they recorded. In addition to the expected birth/death/marriage records, the Friends recorded members’ movements and various actions or behaviors in which members might engage.

According to this list of Quaker abbreviations found on the Indiana Genealogy website, INGenWeb.org, the Friends recorded disciplinary actions and infractions like “deviation from plainness of dress” (dp) or “using profane language” (upl) in addition to movements between congregations, known as Meetings.

The key to understanding how this applies to the Dyer family lies in understanding that a member of a Meeting did not “officially” leave the Meeting until they gave written notice asking to be removed from the rolls. When Ruth’s father, George H. Dyer, moved from his home state of North Carolina to the western states of Indiana and Iowa, the Society in Stokes County, North Carolina, continued to record events related to George and his family.

This was helpful, of course, because if not for the Society of Friends, I might not have found evidence to support George’s biography at all. But I had to do some digging to figure out how to interpret the records that have been digitized, and piecing it all together can lead to a series of outbursts that might draw an “upl” reprimand from your local Meeting.

Interpretation of the Records

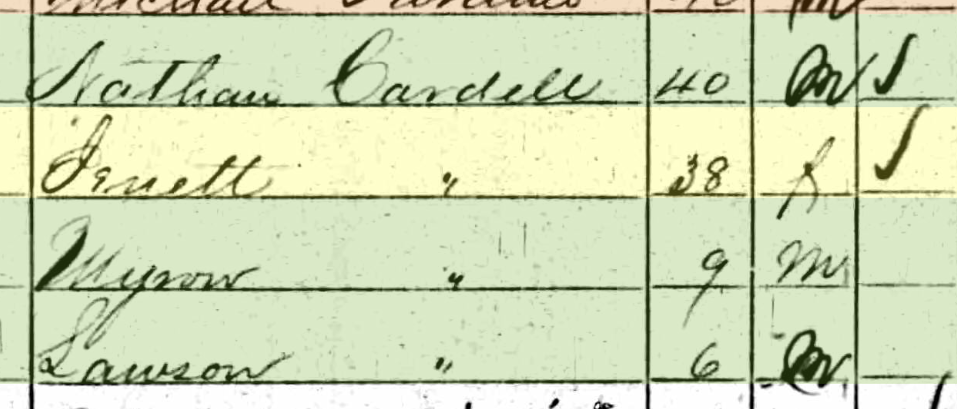

I began with Ruth, so my task was to find records to tell me about her parents. Her 1852 marriage records established her maiden name as “Dyer” – and she was married in Marshall County, Indiana. I soon found a record on Ancestry that gave me her date of birth and the names of her parents – George and Elizabeth – but confusingly gave her birthplace as “Guilford, North Carolina” and her residence as “Wayne County, Indiana.”

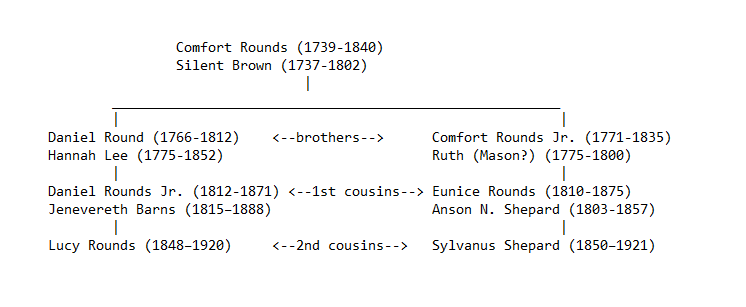

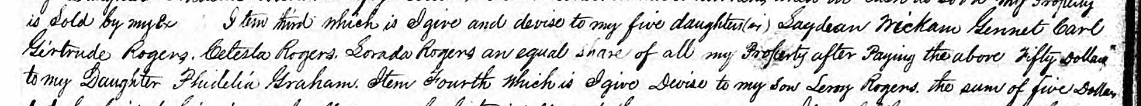

North Carolina marriage records show that George H. Dyer married Elizabeth Willetts on 15 Jun 1822 in Stokes County, NC. The U.S., Hinshaw Index to Selected Quaker Records, 1680-1940 gave me a record showing George, Elizabeth, and their first three daughters (and all five birth dates) recorded in the New Garden Monthly Meeting. That source placed the New Garden Meeting in Wayne County, Indiana.

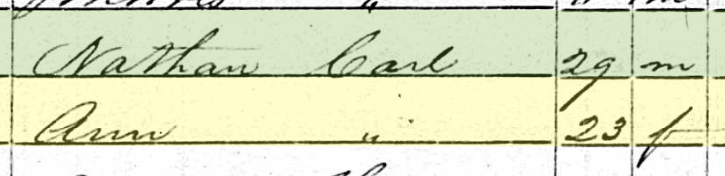

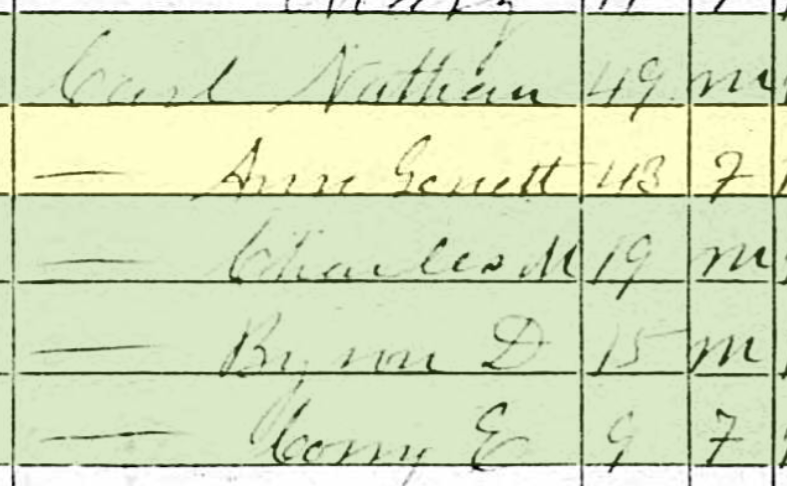

Knowing this led me to inspect the records turning up in both Indiana and North Carolina more closely, and I soon found this record from Ancestry’s U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935, which listed seven children born to “George and Elizabeth Dyre” with birth dates for all nine people, and county of birth for all of the children. The first three daughters clearly matched the three daughters in the New Garden record, and this new record was reported to the Dover Monthly Meeting.

Friends Meetings are organized around an annual and monthly calendar, so records are usually sourced to (for example) “Dover Monthly Meeting” under the state “North Carolina Yearly Meeting” – and the Monthly Meeting should identify the “Meeting County” – in this case, Guilford County, NC.

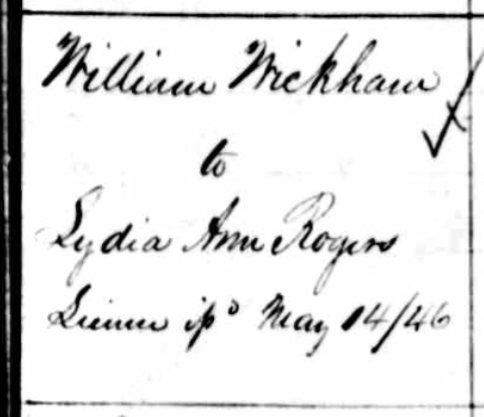

An 1839 entry in the Dover Monthly Meeting reported that the Meeting had received a certificate of marriage for George Dyer and Eunice Bishop from the Chester Monthly Meeting, and the “Society of Friends Records, 1803-1962” resource on IndianaHistory.org, told me that the Chester Monthly Meeting was also located in Wayne County, IN.

More to the Story

Now that I’ve learned enough to understand what the records are telling me, I have a lot of work left to do to untangle the facts and find the details that are left out. None of the records I have so far tell me when people died, but it’s pretty clear that Elizabeth died around 1837 – and several of the children for whom I have birth dates don’t show up in the household in 1850. Some of the children who are in that record may be from Eunice’s first marriage.

There is a lot of exciting historical context implied by all of this, too. The Quakers in Wayne County were active abolitionists and helped escaped slaves find their way to freedom via the Underground Railroad through their county. I don’t yet know enough to tell whether the Dyer family was involved, but maybe that will be a story for another day.