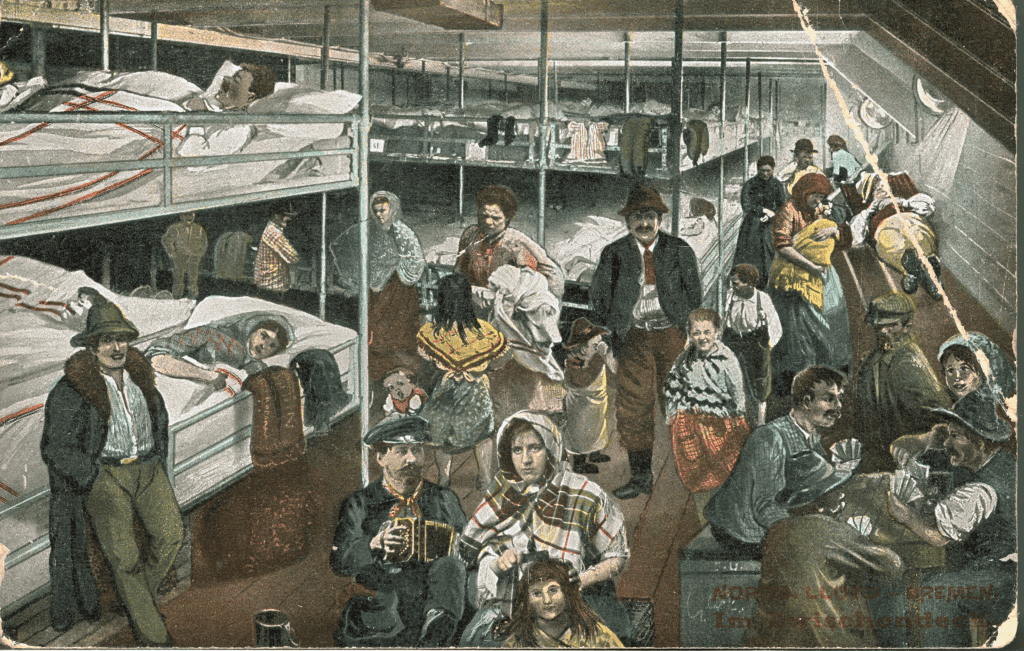

Note: Today’s featured image comes from the Baltimore Immigration Museum’s collection. Today’s family arrived in Baltimore aboard a bark named Blucher in 1854. Learn more about their experience at that link.

Nobody likes to feel ignorant. This is why we are driven to learn. But no one ever truly knows what they don’t know, and sometimes the sense of remaining ignorant no matter how much one learns might compel someone to simply stop learning.

When you go digging into your family history, the things that you don’t know can take on unexpected dimensions and layers due to changes in language, geography, or governments over time. Sometimes, evidence that suggests an ancestor moved a lot may prove later to show that they lived in a place that changed names or was claimed by more than one government. Records we need may not materialize until after learning about someone’s origins, or figuring out how their name might have been misspelled. And we may never find a clear record of where they came from if the name of the place they came from changed between their birth and their emigration.

In other words, researching ancestors who came to America from Europe in the middle of the 19th Century can reveal our ignorance in ways that might seem designed to give us only wrong answers.

So we need to learn to be flexible in our thinking, be willing to review our assumptions, and be prepared to forgive those who came before us for being ignorant of the things we’re trying to learn.

Who Was John Slight?

It would be easy enough to simply say, “John Slight was a German immigrant who arrived in Baltimore in 1854 and anglicized his name to assimilate,” but that leaves out a lot of interesting details that make his ancestry harder to trace.

If you go by his headstone, found in the Oak Wood Cemetery in Ackley, Iowa, John Slight was born (Geb.) in December 1834 and died (Gest.) in June 1879. Of course, the records that tell us his story rarely render his name the same way twice. He could appear as “John,” “Jan,” or “Johann,” and as “Sligt,” “Slahet,” or “Sleight,” depending on how the clerk recording his information perceived his name.

We learned a bit about the Slight family in “Family Reunion: Slight” and we looked at some of those documents and learned a bit about the history of John’s place of origin in the village of Tergast.

The records we have say the Sligt family lived in the village of Tergast, which is located a few miles east of the city of Emden. Emden had been annexed by Prussia in 1744, some 54 years before Jan [John’s father] was born. It was then captured by French forces in 1757, during the Seven Years’ War, and by Anglo-German forces in 1758. In 1807, when Jan was about 9 years old, East Frisia was added to the Kingdom of Holland, which had been created by Napoleon Bonaparte a year before to control the Netherlands. After Napoleon’s downfall in 1815, East Frisia was transferred to the Kingdom of Hanover, which was officially ruled by George III, the king of England.

All of this is to say that while John Slight seems to have been a speaker of the German language, and came from a place that we now identify as being in Germany, the Sligt family might not have been German, and may have even spoken one of the Frisian languages recognized in that part of Germany.

The original Frisian people were descended from tribes of Angles and Saxons (you may equate the term “Anglo-Saxon” with England, but those were Germanic tribes) and they lived in a boggy, marshy territory around Emden that resembled the Netherlands more than other parts of Germany. It might be fair to say that some of the patterns we see in the way John Slight’s parents, grandparents, and aunts and uncles were named more closely resemble the patronymic system used by our Scandinavian ancestors, than you might expect from more traditionally German families.

The point here is that Germany itself has only been Germany since 1870, and when people came from places that were Germany later, they could be labeled with a variety of names that might or might not be helpful. We were lucky to see “Tergast” on the Sligt family’s immigration documents, because when we see documents that say they were from Germany, Prussia, or Hanover, we know that Tergast was, technically, part of each of those larger places during John Slight’s childhood.

The Slight Sweden Diversion

On March 23, 1856, Ogle County, Illinois, John Sligt married Margaret Sweden, according to the Ogle County marriage records.

Margaret’s full name was “Frauke Margrette Swidden” or “Sweeden” (depending on your source) and unless you know to look for a variety of spelling permutations for each of her three names, you will miss her in the records. Many county clerks or newspapers that rendered her name would drop “Frauke” and list her as “Margaret” (as that marriage record did). But many documents, and her headstone (shared with her husband, seen above) indicate that she was called Frauke, which is a German diminutive for “frau” that means something like “little princess” or “little wife”.

Unfortunately, that name is frequently mis-recorded or mistranscribed as “Franke” or some similar variation.

Fortunately, once you know what to look for, it is relatively easy to connect Frauke to her parents and siblings with a variety of documents. There are immigration records and German-language newspaper accounts of the Swidden family leaving Emden aboard the Antje Brons, and from there you can begin to piece together Frauke’s ancestry.

But once again, the “Americanization” of names complicates our search. For example, Frauke’s father was Marten Gerjets Swidden, born in 1805 and residing in Osterhusen, in Ostfriesland, when he and his wife’s family, the Boyengers, decided to migrate to the New World. His grave marker renders his name as “M.G. Sweeden” but he often appears in records as “Martin George Swidden” or similar.

But that middle name, Gerjets, is not a German version of “George.” The German name for

George is “Georg,” though that can also be rendered as Jörg, Jürgen, or Jörgen; all derived from the Greek name Georgios, meaning “farmer.” Gerjets, though, is an old East Frisian surname that means “son of Gerjet,” and is usually a surname. That name is derived from the German word, ger, meaning “spear” or “dart.”

So the question is, did Marten choose to change “Gerjets” to “George,” or was that choice made by a clerk somewhere down the line because the two names sounded similar to him? It’s hard to say.

What Did We Learn From All of This?

There are a lot of specifics in the records of the Slight and Sweeden families that might not directly apply to your “German” families, but there are a few broadly applicable tips that will at least help you learn about your ancestors’ specific difficulties.

- Pay attention to how their birthplace is recorded. If the record is from before 1870 and it just says “Germany,” that could refer to any number of places throughout Europe – including modern Poland, Austria, Czechia, or really anywhere German was spoken widely, like France or Switzerland. If the record indicates more specific principalities (Prussia, Hanover, Hesse) take note of that, and look for more local towns or districts that fall into those areas when you find other records.

- Don’t commit to one “correct” spelling for names. It might be tempting to dismiss the different spellings you find as mistakes, either on the part of the immigrant (who might or might not be literate in English), the clerk (who might have assumed the immigrant was illiterate), or transcribers (who might see the “u” in “Frauke” as an “n”). Do your best to document the various spellings and pay attention to where they turn up; they may help you figure out that a “German” family actually spoke another language or belonged to another ethnic group, which could help you trace further back.

- Use the variations to find more records. This is tricky, because if you have to use fuzzier spellings or leave off a unique name (like “Frauke”) in favor of a more common name (like “Margaret”) you will get a lot of false positives. If you are able to identify her family members, you can use those relationships to help sift through those false positives and find what you’re looking for. (This is also where using the FAN Club techniques can help you.)

And this last tip isn’t as much about genealogy as it is about current events: studying these immigrant communities has compelled me to be more gracious about how I view modern immigrants.

The super-heated partisan discussions over immigration policy that have driven the dialogue over the last several decades often assumes that our European ancestors came here “the right way” and assimilated into “our” culture – but the reality is that they frequently came over with nothing, just showed up and brought whole villages of relatives with them, and took several generations to “assimilate,” which sometimes meant losing their native language and changing their names to fit in.

But we can also see from the language on their headstones and their persistent use of “family names” that the towns and counties they inhabited had to learn to accept them and their “foreignness,” too.

And that is a lesson in grace that more Americans need to embrace.

Say hello, cousin!