For those of you reading this in the far future, the second “No Kings” rally was held last Saturday. My wife and I are both U.S. Air Force veterans, and the small, non-partisan grass-roots veterans group we belong to was invited to speak at the rally in San Antonio. Our speaker closed by evoking our shared anti-fascist family history:

I stand here with the ghosts of my grandfathers at my back, brave men who fought fascism in the Army and the Army Air Corps during WWII. We, brothers and sisters and siblings, in uniform and out, we volunteered to share the burden of protecting democracy, promoting justice for all, projecting the best of us for the world to see. The Constitution we swore to defend is calling upon us again. And I cannot ignore the call to stand up and answer this administration’s chaos, fearmongering, and open displays of hatred with this reminder of why we serve.

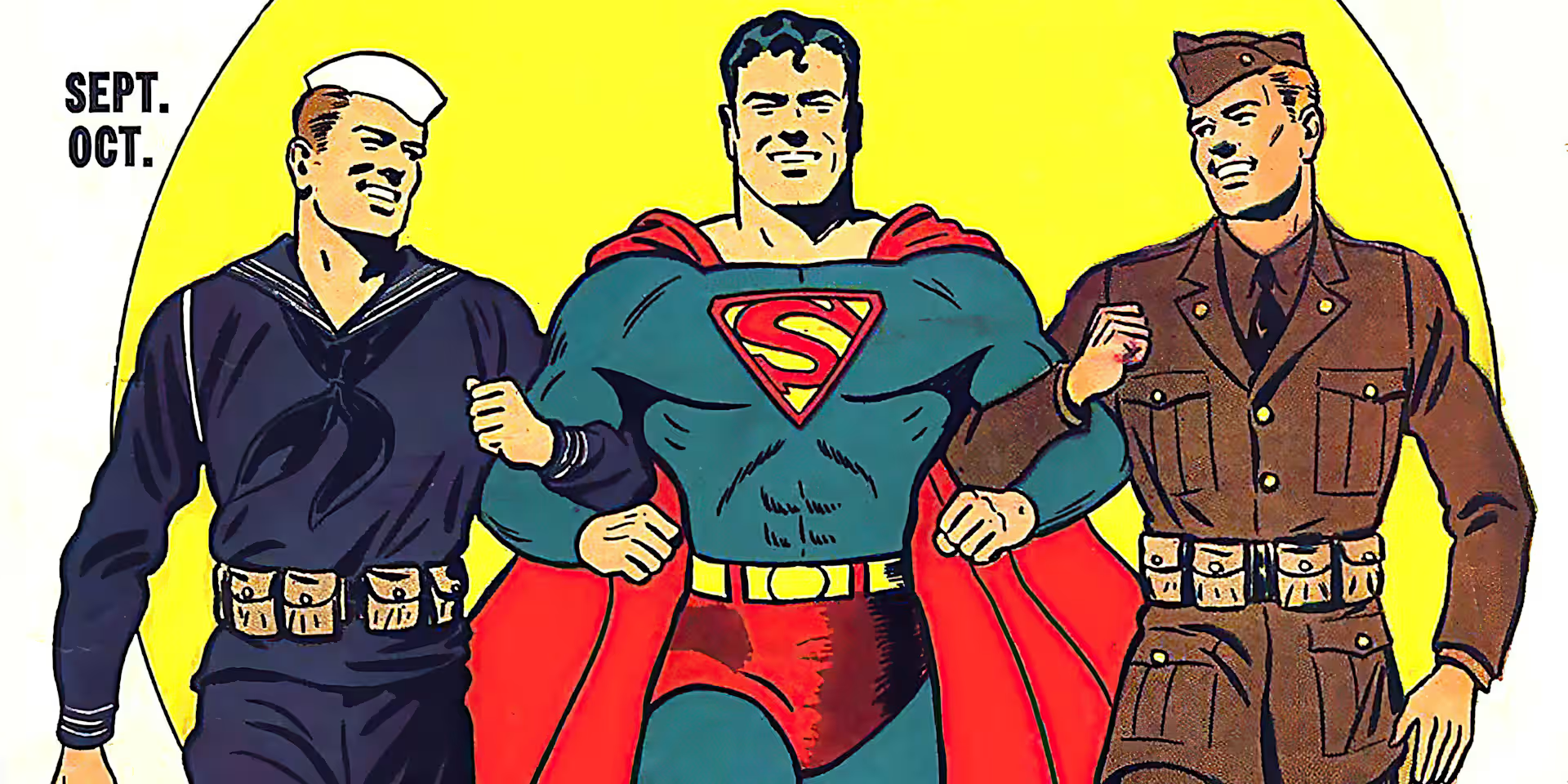

My family is proud that all four of our grandfathers played a role in stopping Nazi Germany from creating an empire based on European Christian nationalism and fascist-style dictatorship. But at the time, before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Americans were starkly divided over the question of whether America should join the war, and on which side. Fascist and pro-Nazi Americans rallied around an “America First” policy, arguing for an isolationist position of neutrality that would have allowed the Axis Powers to overtake Europe and Russia. Many of those Americans bought into pseudo-scientific ideas of a Christian, European “superman,” a master race, that had the right to rule over everyone else.

But others in America had a different idea about what a Superman should be.

The comic book Superman embodied “truth, justice, and the American Way” – a useful propaganda tool for reminding people that the American experiment was about preserving democracy, a system with flaws, but one that rooted political power in those being governed.

There has never been a simple binary of political thought in America, even during World War II. But when push comes to shove, we have, as a nation, historically chosen to fight for more democratic ideals. And the reward for defending those democratic ideals has generally led to more prosperity, less violence, and more equality for the citizens of democracies.

That support for democracy is supposed to be the foundation for all of the things that have made our society more free, more equal, and more prosperous – but it would be a mistake to pretend that significant numbers of our own citizens disagree strongly with the notion of democracy and the concepts of self-government.

Not Our First Conflict

American involvement in World War I was far smaller that World War II, and my own family’s involvement was smaller, too. My great-grandfather, Dick Witter, enlisted in the Army and was stationed at the training base near San Diego, California1; but he never went overseas or saw combat. Few of my distant cousins did. But that war did represent the first time that America was seen as a major influence on world events.

One of Kate’s ancestors was Frank Shuffler, who was too old to enlist in World War I, but was killed in a train accident after taking a job with the railroad to make up for the number of young laborers who did enlist. We touched on Frank’s story, and on the part the railroads played as America began growing into a world power in The Ballad of Mrs. Steele.

And all of that growth and development only began after the war that was fought over the existence of slavery.

The War Between the States

When you reduce all of the arguments about the causes of the American Civil War down to the most basic question, that question is: does any person have the right to own another as property?

After the Revolution, and the ratification of the U.S. Constitution2, Americans struggled with the contradictions inherent to any democratic form of government. In the states that allowed slavery, those with the power to own others argued that it was their God-given right to do so. Even though the secessionist movement leading to the Civil War saw themselves as resisting a tyrannical federal government in Washington that deprived them of their rights to their property (ie, other people), many of them sought to restore a system in which those who own land own the labor of those living on that land.

Many of my ancestors fought to preserve the Union, and to establish basic, fundamental rights for every individual. Even though many of them personally held segregationist views and believed that the freed slaves could not live side by side with white Americans3, they still fought for the principle of individual freedom. Just a small sample:

- John Henry Callin, 21st Battery of the Ohio Light Artillery (author of War Poems) and his brothers:

- George William Callin, 21st Battery of the Ohio Light Artillery (author of The Callin Family History)

- James Monroe Callin, 67th Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry

- John Riley McCullough, 1st Regiment, Indiana Heavy Artillery Battery

- Joel Clark, 45th Regiment, Kentucky Infantry

- Jacob Edward Opp, 13th New York Infantry Regiment

- Joseph Frey, 5th Regiment of Infantry

Of course, there was one exception, that of John Shaw May, who was commissioned in the Confederate 6th Regiment, Kentucky Cavalry. (See Dangerous Times in Kentucky for that story.)

The Original “No Kings” Event

And, of course, the more I dig, the more I uncover ancestors who played a role in the American Revolution. People who risked far more than anyone marching with a snarky sign surrounded by inflatable cartoon costumes.

James Callin, of course, as well as James McCullough, William Bowen, and even a Hessian soldier who decided not to go back to life under a king after being held as a POW in New Jersey, Leopold Zindle.

There are those today who try to argue that only people whose ancestors were here for these wars can be counted as “real” Americans, or “heritage Americans.” Many of the descendants of these men would like to hold them up as heroes and claim a piece of their valor to justify choices that undermine the foundational principles of democracy that they all fought for.

I can’t do that.

I can be grateful that they fought for their principles, and acknowledge that my life has been better than it might have been had they not fought, and not won, their battles. But I can’t claim their valor as my own, and I can’t pretend that they were anything other than the flawed humans that we all are.

If my theory about James Callin is correct, then he participated in the last battles that drove the Shawnee, Delaware (Lenape), Miami, and Wyandot people from their ancestral lands. And before fighting in the Civil War, Joseph Frey (newly immigrated from Germany) fought in the Mexican War that helped the slave-owning Texans move the U.S. border on nearly 80,000 Mexican citizens and a large but unspecified number of Native Americans. These events are a part of U.S. history that modern Americans are ashamed to talk about. Our history of accepting slavery and the violence that followed Reconstruction poisons our political discourse to this day.

But despite their mistakes, the world my ancestors fought to give us is one in which each individual has rights. The government those individuals choose, using the rules agreed upon in the Constitution, is supposed to derive its power from those people, and use its power to preserve those rights.

Today’s government was barely elected by a plurality of voters – and the current administration’s actions since taking office certainly resemble the grievances against the King of England that led my ancestors to fight in the Revolutionary War.

I believe to my core that there is a peaceful resolution available to us, and it’s in the Constitution that I swore to uphold. It will require courage from elected officials, many of whom are not known for their willingness to put their voters ahead of their donors. But that solution is still there, and that is why I will continue to demand it from my representatives.

And even if you don’t have a pedigree of American soldiers like mine, if you’re an American now, you should demand that, too.

- See Grandma Merle’s Travelogue where she talks about Dick’s time in the Army. ↩︎

- I highly recommend that you read Pauline Maier’s book, “Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788” sometime. It reviews the arguments made for and against the ratification of the Consitution in each of the original 13 states, using press and pamphlets from that time period. Some of those arguments will sound painfully familiar to modern readers. ↩︎

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr. published “Lincoln on Race and Slavery” and it is eye-opening to see how the Great Emancipator talked about these issues in his speeches and letters. ↩︎

Say hello, cousin!