Taking stock of the journey so far

We have been climbing a ladder of evidence for a couple of months now – a metaphorical ladder leaning against the side of one of my “family palm trees”. The first several rungs felt like very solid footing, but the last three have been increasingly shaky. Depending on who you are and what your skill level is, you might have a different comfort level with the conclusions I’ve accepted along the way and I want to take a moment to address that before moving on.

Evidence Standard

You may have run across several different “rules of three” in other fields, but when I use it in this post, I’m referring to a standard for judging whether a piece of evidence should be included in the profile you are building for your ancestor. The standard is that at least three points of comparison (three facts) in the new document or narrative you are evaluating should match what you already know about your ancestor. I want to be crystal clear: this is not a standard for proof. It is a standard for judging whether a document is even about your ancestor.

Almost every document will have the person’s name – that is almost always the first of the three facts to compare. Other facts will depend on the document you’re examining – date and/or place of birth/death/marriage, names of parents or siblings, addresses, and identification numbers (like Social Security or service numbers in more recent generations) can all add up and help identify a unique individual. The rule is that if three facts match each other (name, date of birth, and place of the event; name, relatives’ names, and time frame; gender, birth event, and parents’ names, etc.) that indicates that you can add the information in that document to “what you know” about that individual. Again, this isn’t “proof” but it is a way of figuring out which puzzle pieces belong in your ancestor’s picture, and can tell you where to look for more pieces.

Being appropriately skeptical means that any new evidence you find should be judged against what you already know – and if the facts don’t add up, you should be mentally prepared to change your mind about what you thought you knew, depending on what all of the evidence tells you. I would give you a specific example, but this whole series of posts is meant to be that example.

Types of Evidence

If you aren’t already familiar with the terms “primary source” and “secondary source,” there are a lot of good resources out there for learning more. (This page is a good start.) The most important thing to keep in mind is that the terms “primary and secondary” are not the same as “correct and incorrect” or “right and wrong” – one is not “better” or “more reliable” than the other.

For example, last week’s post about “An Old Man’s Memory” talked about a book that collected the firsthand knowledge of William Whitford. William’s book could be seen as both a “primary” source because he was a firsthand witness to events he documented, and as a “secondary” source, because some of the information he recorded was told to him by his parents and his older relatives.

Over the next couple of weeks, I’m going to be looking at several secondary sources – compiled lists of vital records (not the original records), family histories published by genealogical researchers, and local histories. Some of these published sources offer a tantalizing amount of information but can be disappointing in relevance and/or quality.

What Is Our Goal?

I started this series hoping to confirm a direct ancestor connection to a specific person – the surgeon, John Greene, of Rhode Island. The evidence supporting my case is thin, at best, and depends on several assumptions that might not be “provable” with existing documents. I keep going because I have not found evidence that contradicts what I have pieced together. I may need to plan a trip to Rhode Island to seek out un-digitized documents at some point, assuming I can figure out whether such documents exist.

If my goal was to prove my case now, with the information I already have, I would have to stop. But my goal is to assess the work done by myself and others for weaknesses – and so far, what I have learned has encouraged me to continue investigating. There are leads; there are clues.

I would love to find solid, documentary evidence in vital records that allows me to declare Rungs 4 and 5 “confirmed” – but I have found evidence that suggests that isn’t likely to happen. In 1972, Burton Bernstein published a book called “The Sticks: Profile of Essex County, New York,” portions of which had originally appeared in the New Yorker magazine. According to Bernstein, “General Washington made a victorious inspection of both Crown Point and Ticonderoga in 1783, but what he saw was mostly sad ruins. Crown Point quickly reverted to pastureland and Ticonderoga was disposed of in a grant to Columbia and Union Colleges by the new State of New York.”1

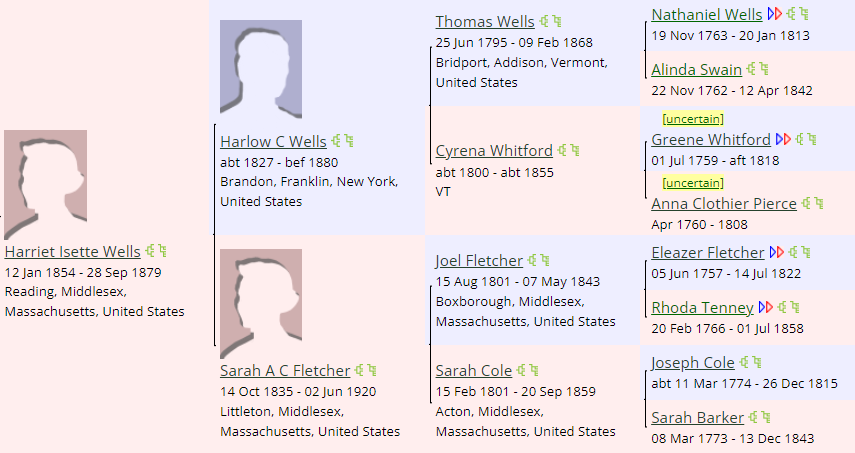

According to the records we do have, Greene Whitford and his family lived in Brandon, Vermont, in 1788, in Hampton, Washington County, New York, from 1799 to 1801, and in Crown Point from about 1803. We have seen the evidence that his daughter was born in Crown Point. Her name doesn’t show up reliably (Cyrena/Irene/Anna, depending on the source), but we also know that women were poorly documented at that time – census records at all levels (local, state, or federal) only listed the heads of households, and remote or rural areas were slow to begin documenting vital records with any regularity.

All of this explains why there are no definite records tying Harlow Wells to his likely grandfather, Greene Whitford – and the remoteness of the area suggests that his family was the most likely origin of Cyrena and Harlow. “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” – but until we find more evidence, I will continue.

Hopefully, I’m getting into families that have been researched by other descendants, and if you are one of those who have trod this path before, I’d love to hear from you.

Next week, we’ll continue up the trail, seeking firmer footing. Join us!

Bernstein, Burton, “The Sticks: A Profile of Essex County, New York”; Dodd, Mead – New York; 1972; pages 37-38, accessed at Archive.org on 4 Feb 2024.

Say hello, cousin!